4 Ways AI Can Hack Literature

If you haven’t yet, you really should read this essay by Hilarius Bookbinder:

This is an excellent and insightful example of the problems of modern education. In fact, even my 14-year-old daughter told me that her classmates in Middle School tend to act just like this.

AI has its uses and misuses. In fact, Annie Kreighbaum is right:

But that doesn’t mean that you should just leave AI alone. In fact, if you use it the right way, AI can help open up new worlds of insight — especially when it comes to translation.

Let’s take a look at something from outside the world of Dream of the Red Chamber for a minute.

Over a decade ago, I bought this excellent copy of 唐詩三百首 (Three Hundred Tang Poems):

You can tell it’s a genuine photo because of the awful glare.

Anyway, the cool thing about this version — and all books in this “new translation” (新譯) series published by Sanmin (三民書局) — is the long and detailed amount of notes in Chinese. Every poem looks sort of like this:

You’ve got the poem on one side, followed by an extensive introduction to the poem, a description of the 仄 and 平 rhyming system, a gloss of all difficult terms, a translation into modern Chinese, and an extensive commentary on the meaning and philosophical insight that comes from every poem.

Now, that’s pretty cool stuff — though it can also be pretty scary if you’re an ignorant foreigner like me.

However, if you use it right, you can not only get the same level of insight from AI, but you can actually exceed what you get from this book.

So let’s take a quick look at the poem in question and what AI can tell us about it.

1. Quality Translation

I’m going to use DeepSeek for this task.

I don’t think DeepSeek is necessarily better or more capable than, say, ChatGPT or Gemini or Claude or whatever. However, in my experience DeepSeek tends to do just a little bit better with Chinese texts.

The poem we’re going to cover today is this classic by Li Bai (or Li Bo, depending on whose side you’re on):

《下終南山過斛斯山人宿置酒》 李白

暮從碧山下,山月隨人歸。

卻顧所來徑,蒼蒼橫翠微。

相攜及田家,童稚開荊扉。

綠竹入幽徑,青蘿拂行衣。

歡言得所憩,美酒聊共揮。

長歌吟松風,曲盡河星稀。

我醉君復樂,陶然共忘機。

Thanks to Wikisource for the text in traditional Chinese.

Now, before we go any further, let’s look at a few translations. First comes the well-known Witter Bynner translation, from The Jade Mountain: A Chinese Anthology, originally published back in 1929.

Next comes a more modern translation from Xu Yuanzhong in 300 Tang Poems: A New Translation. This is from the

That gives you an idea, right?

Anyway, I asked DeepSeek for a translation:

And this is what it gave me:

"Descending Zhongnan Mountain, Visiting the Recluse Husi, and Staying for Wine"

by Li Bai

At dusk I left the jade-green mountain high,

The moon walked with me as I homeward went.

Turning, I gazed on the path from the sky,

Layered in azure, veiled in mist’s descent.

Hand in hand, we reached the cottager’s gate,

Where children rushed to part the thornwood door.

Through dark bamboos wound a path serene and straight,

Vine leaves brushed my robe as we walked before.

Gladly I found a place to rest my feet,

With fine wine shared, our cups flew free and light.

We sang to the pines as the winds grew sweet,

Till songs were spent under stars fading bright.

Drunk, I rejoiced in my host’s delight—

Lost in bliss, all worldly cares took flight.

Now, if you compare the DeepSeek version with both the original and the other versions, you’ll notice that a few things stick out beyond just the rhyme scheme:

碧山 is almost certainly “jade green mountain,” since 碧 is either “green jade” or a bluish green color. “Blue mountains” is also acceptable, and probably works better in English. But “hills” doesn’t work.

荊扉 literally means “thorn door.” “Thornwood” in the AI translation works nicely, as does “a gate of thorn” in the Bynner translation. “Gate” alone kind of works — but it’s not the same rich image that Li Bai has written.

聊共揮 is much better rendered as “our cups flew free and light” than as just being glad to drink. 揮 is to wave around (i.e. a sword), and 聊 is to chat; of course, instead of just saying “talk,” you can imply this by describing the riotous act of drinking, which DeepSeek does quite nicely.

陶然共忘機 is also excellently translated as “lost in bliss, all worldly cares took flight.” Bynner’s “between us we forgot the world” is also an excellent rendition of this.

Now, I shouldn’t be too harsh here. There actually are parts where the AI translation isn’t great.

青蘿拂行衣, for example, is rendered by DeepSeek as “vine leaves brushed my robe.” “Brush” kind of works for 拂, but I prefer Xu Yuanzhong’s “vines caress my cloak with glee.”

And I suppose this means that you should be careful before you simply take the translation at face value. However, the speed and accuracy of DeepSeek’s poem, not to mention the fact that it has an actual rhyme scheme, is quite impressive.

But, if we left it at this we wouldn’t learn much, would we? There’s more depth to this poem, and AI can help us figure out what even its own English translation doesn’t show us.

2. Digging Deep

I’ve learned that the best step in literary criticism is to start asking questions.

Let’s say that we understand every word in this poem in Chinese. However, since we’re ignorant foreigners, we’re having a hard time understanding just why it’s so famous and beloved.

Let’s see if we can figure it out by simply being curious.

I asked DeepSeek why Li Bai would use that phrase 碧山 and what it symbolizes:

The answer to this simple question starts to reveal the depth behind this poem that is difficult to understand from the translation alone:

DeepSeek’s answer consisted of four parts:

Jade green represents nobility, immortality, and spiritual purity. It’s a very natural color — a welcoming landscape, as opposed to a rocky mountain. The mountain becomes celestial in this sense.

The mountain is also a spiritual retreat, associated with recluses (which DeepSeek kindly and correctly identifies as 隱士).

The jade mountain is a contrast with the mundane world, which Li Bai identifies as 田家, or his friend’s rural home.

And, of course, Li Bai loved painting himself as a wanderer between the immortal realms and the worldly.

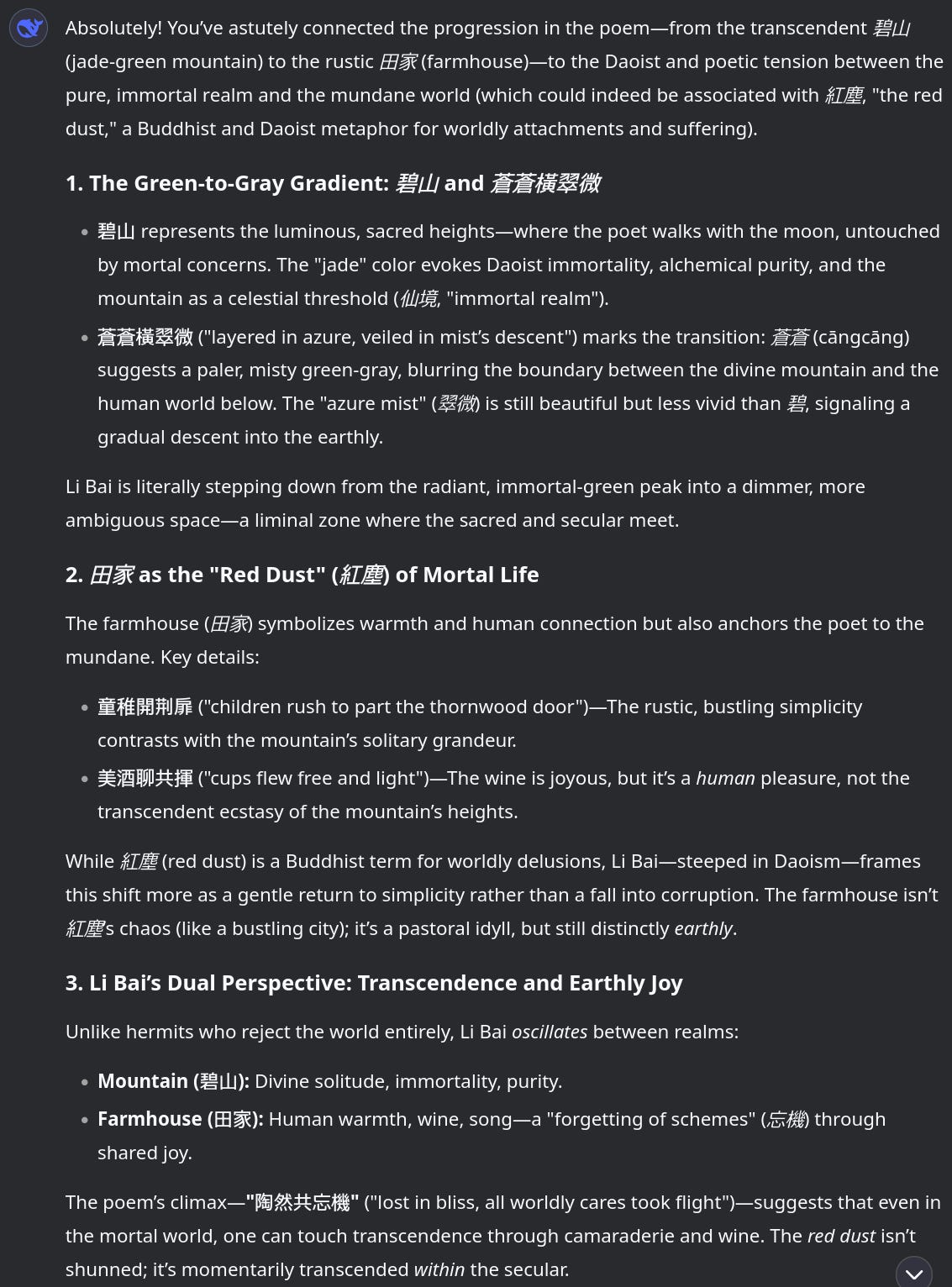

We can even go a step further. When we look at the poem, we can actually see Li Bai journeying through the green mist into the rocky world below. And, when we ask DeepSeek about it, it tells us the answer right away:

What we learn here is that 蒼蒼 is kind of a lesser green than the radiant 碧 — and now we can see why “blue mountains” simply doesn’t work. The next phrase, 翠微, is clearly lesser than that, and so on and so forth.

What we’ve established here is that Li Bai isn’t just taking us on a drunken revelry, but, rather, that he’s taking us on a transcendent journey from the immortal realm down to the mortal.

And, in the end, 陶然共忘機, right? We can all achieve that same transcendent moment by enjoying the bliss of good wine and good company, letting the worldly cares go away.

3. Learning The Language

Now, knowing what the poem means and what it symbolizes really isn’t quite enough. There are also some opportunities here for us to learn the language of Tang poetry. And, interestingly enough, AI can sometimes help us figure out what the dictionary doesn’t tell us.

The last word of the poem, 機, is actually kind of a difficult one to understand. Wiktionary (which is like taking all the good Chinese-English dictionaries and merging them together) gives 14 possible definitions, none of which seem to fit:

It’s even worse, of course, if you use A Student’s Dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese:

When I first bought a copy of this dictionary several years ago, it almost caused me to stop trying to study classical Chinese. While the examples are excellent, the definitions are so broad and are so disconnected from example sentences as to be practically useless.

I mean, is 機 here the “crux?” Is it the “opportune moment?” It’s surely not “dexterity” or “skill,” nor is it a loom, right? Maybe it’s a mechanism?

Now, in my opinion, this is where the true power of AI as a learning tool shines through. Let’s ask DeepSeek what in the world is going on with 機:

And, of course, it turns out that we were right:

Now, we probably knew from the translation above that 機 meant something like the system, the world, or the opposite of the idea created by 碧山. However, this explanation is incredible. In fact, it connects this poem to a Zhuangzi parable:

有機事者必有機心。

Those who use mechanical devices must have scheming minds.

And that use of 機 fits in with our usage here brilliantly.

That’s the power that AI has. It’s more than just a way to summarize an article or give you a few ideas for your next post or whatever. If you start poking it a little bit and digging deep, you’ll find that it makes some fascinating connections with the entire literary cannon — as if you had an encyclopedia that could talk to you.

4. Breaking The Rules

Now, if you had a good Chinese teacher and the right textbook, you could absolutely figure all of this out yourself. It might take a while, but you could do it.

However, the best part about AI is that you can start breaking the rules.

You see — the problem that the kid had in the Scriptorium Philosophia post above is that he didn’t even try to read. He went to the very first step, figured that was good enough, and didn’t dig deeper. He wasn’t curious, and he got an answer that was clearly completely AI generated and was worthless.

He learned nothing, his teacher caught him, and he deserved to fail.

But, if you actually take the time to read, and you start trying to make connections where connections don’t belong, you might come across some pretty interesting insights.

I always tend to go back to Goethe’s Faust. It’s my favorite German composition, and there are certain scenes and concepts that stick out in my head.

There’s a part at the beginning of Faust, part of the so-called “Prolog im Himmel” (Prologue in Heaven), where the angels Raphael, Gabriel, and Michael are describing the creation of the world. This happens right before Der Herr (The Lord) and Mephistopheles discuss the fate of poor Faust.

The part that came to mind is this, from Gabriel:

Und schnell und unbegreiflich schnelle

Dreht sich umher der Erde Pracht;

Es wechselt Paradieseshelle

Mit tiefer, schauervoller Nacht.

Es schäumt das Meer in breiten Flüssen

Am tiefen Grund der Felsen auf,

Und Fels und Meer wird fortgerissen

Im ewig schnellem Sphärenlauf.

Or, in English:

And quickly and incomprehensibly fast

The earth's splendor turns around;

Paradise's brightness changes

With deep, dreadful night.

The sea foams in broad rivers

At the deep base of the rocks,

And rock and sea are swept away

In the eternally fast sphere's course.

That’s pretty obscure, right? We know that there’s no connection between this poem and the Li Bai poem. They’re not on the right part of the planet, after all. They’ve got completely different religious backgrounds.

However, we can ask DeepSeek how they compare. In fact, we can compare the Chinese to the German directly.

Now, I can certainly see some pieces of comparison. But perhaps AI might know better:

Now, if I were to bring this up in a Chinese literature class, the teacher would probably kick me out of the classroom. And I remember receiving bizarre stares when I did try this sort of thing once in a German literary criticism course in college. I learned then that you don’t want to assume that your teacher knows something that she clearly doesn’t know.

But DeepSeek’s more than willing to indulge me — and that’s the craziest part of all.

First of all, DeepSeek catches on to something I overlooked: Goethe’s heaven is the process of creating order from chaos, almost a violent process. Li Bai’s heaven, however, is unmistakably gentle:

Second comes a point I actually disagree with. DeepSeek describes 田家 as a place free from worldly cares; I see it actually quite similar to the “es schäumt das Meer” (the sea foams) that Goethe describes. We’ll come back to this point in a second:

Third comes a point that I didn’t mention at all:

And fourth comes a very simple comparison between the philosophies of Leibniz and Zhuangzi:

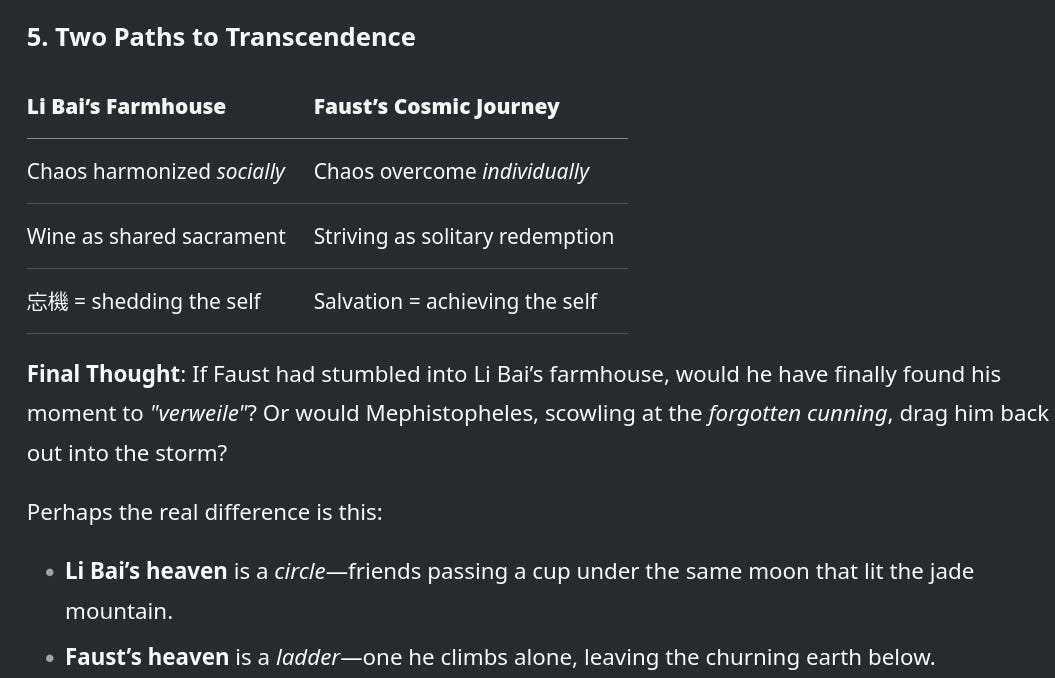

In the end comes a very simple comparison, followed by a question that only the craziest of literary theorists could have come up with:

Now, let’s push back on DeepSeek’s second point, the one I said we’d come back to, and see what we get:

And, as you probably could guess, DeepSeek decided to cave in to an extent, but continued to push back to its main point:

And we could go on and on like this for hours if we wanted to.

Conclusion

See, this is where the real magic and power of AI lies.

It’s not about cheating on your homework and having the AI do all the hard work.

It’s about using AI as a tool for learning, a tool for comparison, and a tool for debate.

If you use it correctly — and it really doesn’t matter which engine you use — AI will help you discover insights into literature that you didn’t even think were possible before.

But it requires you to do a few things:

You need to be curious. You can’t settle for the first answer you get. Read through it carefully, find something you don’t understand or disagree with, and push back.

You need to be able to read it. All AI chat bots will hallucinate. You need to be aware of that, and you need to be able to spot the mistakes it makes. In fact, sometimes you’ll discover that it didn’t make a mistake, and that you were the one who was mistaken. But you don’t get that learning process if you don’t do your homework.

You need to be well read. The more you’ve read, the more interesting this becomes. Spending all your time watching Netflix and letting your volumes gather dust isn’t going to do the trick.

Don’t simply ignore AI or protest against it. It’s here to stay — and, if you learn how to harness its powers, it can bring you to places you never thought you’d be.

But don’t let yourself be satisfied with the first answer it gives you.

This is such a thorough and deep dive! I wish tools like this had been around when I was in school. Everything is explained so clearly, with solid reasoning, and your notation is super clean and easy to follow too.

I feel I understand the first three points, but don't fully grasp point four and what the barrier is to attempting to come up with comparisons between the two texts yourself, even if your understanding of one of the texts is based on the AI translation and analysis. Though maybe I'm neglecting the student angle here, but it still feels a bit like using AI as a short cut past taking the time to think about things and come to your own conclusions.

I enjoy thinking of parallels and points of comparison and contrast between wildly different works, so I wouldn't want to pass up a chance to contemplate it myself. I'd rather write a post myself comparing Anthy Himemiya from Revolutionary Girl Utena to Nora Roberts from A Doll's House than ask AI to do the thinking about comparing them. But maybe if you're curious about parallels with something you know of but haven't read yet there's a use case.

With my own hobbyist research into Aztec mythology I've found plenty of information in books that seems completely absent from the English speaking internet (until I talk about it), so I wonder if AI would be as useful for studies of Aztec culture. There is one notable translation detail in the Florentine Codex I've always been suspicious of that this post is inspiring me to test an AI investigation with, so I'll start from there and see how it pans out.