Granny Liu Discovers Clocks

This is another brief exchange, but shows Cao Xueqin’s literary genius as well. He describes the bewilderment Granny Liu has at seeing a mechanical clock for the first time, but manages to do so without making fun of her or exaggerating her reaction. More on the clocks tomorrow.

My Translation

Granny Liu could only hear a continuous clanking sound, a sound similar to someone striking a gong or the sifting of flour through a sieve. She couldn’t help but glance to the left and the right. She suddenly saw a small box hanging from a pillar in the main hall. There was something that looked like a steelyard weight hanging down from it. It seemed to be swaying wildly without stopping.

“What could this thing be?” wondered Granny Liu. “What could it be used for?”

Just as she was staring in bewilderment, she suddenly heard a loud “clang” as clear as a golden bell or a bronze chime. She was so startled that she couldn’t help but open her eyes wide in fright.

This was repeated eight or nine more times in a row. Granny Liu was about to ask what this meant when she saw some young maids running past her, saying “Wang Xifeng is coming down!”

Ping’er and Zhou Rui’s wife stood up quickly. “Just say seated, Granny,” they told Granny Liu. “When the time comes, we’ll come and get you.” And with that, they went out to meet Wang Xifeng.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

David Hawkes refers to 打鑼櫃篩面 as a “flour-bolting machine” without much more explanation. I’m still not entirely certain I understand what kind of machine this was; as usual, please let me know in the comments if you have any more insight.

Yang

The Yangs follow the Hawkes translation in using the phrase “flour-bolting machine” word for word. Unfortunately, neither translation mentions how interesting it is to see Granny Liu think things like “有煞用處呢” in the same paragraph that contains more classical, descriptive phrases like “陡聽.”

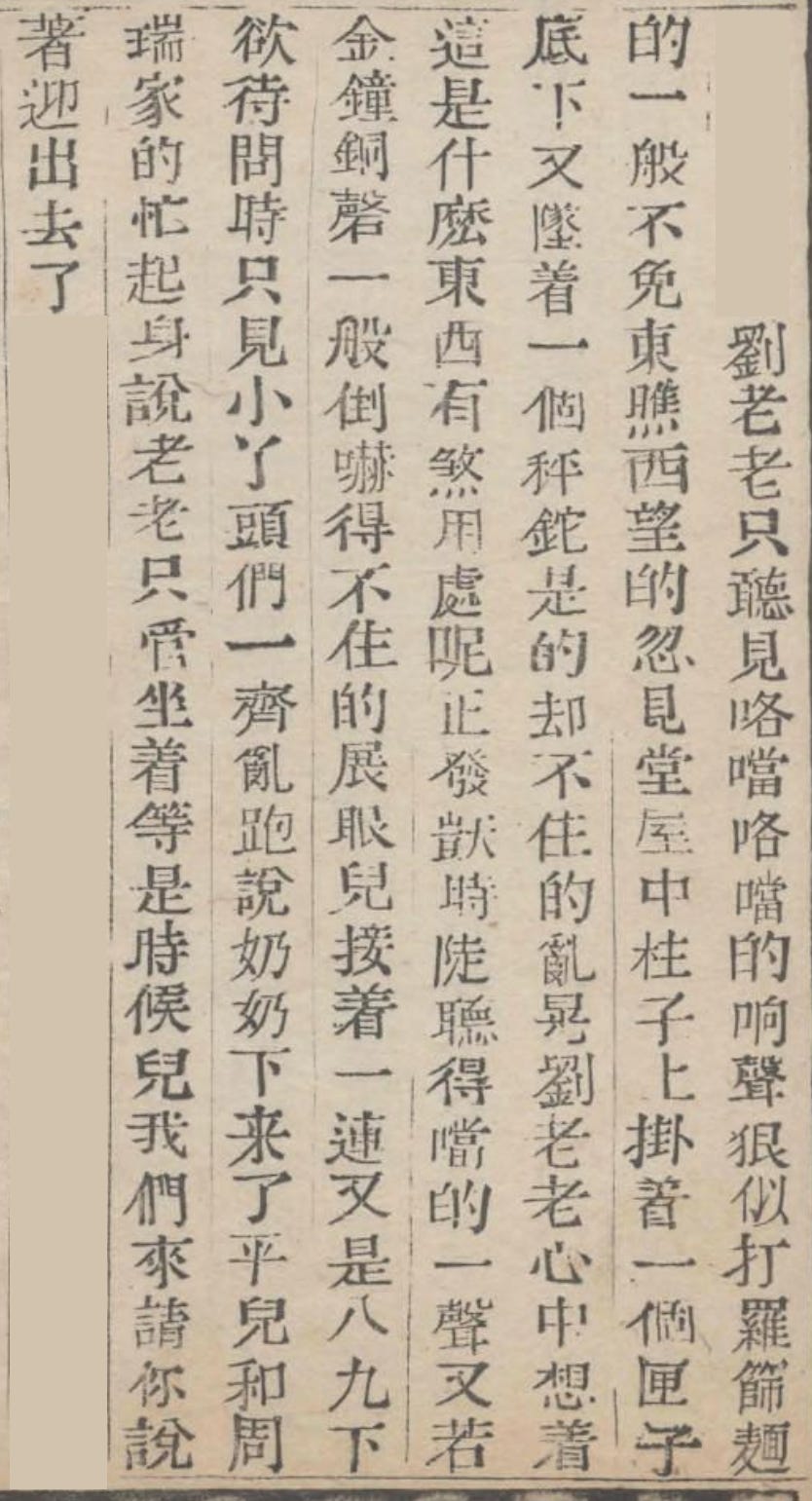

Chinese Text

劉姥姥只聽見咯噹咯噹的響聲,大有打鑼櫃篩面的一般,不免東瞧西望的。忽見堂屋中柱子上掛著一個匣子,底下又墜著一個秤砣似的,卻不住的亂晃。劉姥姥心中想著:「這是什麼東西?有煞用處呢?……」正發呆時,陡聽得「當」的一聲,又若金鐘銅磬一般,倒嚇得不住的展眼兒。接著一連又是八九下。欲待問時,只見小丫頭們一齊亂跑,說:「奶奶下來了。」平兒和周瑞家的忙起身說:「姥姥只管坐著,等是時候兒,我們來請你。」說著,迎出去了。

Translation Notes

咯噹 (gēdāng) means a clanking sound.

打鑼 means to strike a gong. I think the 櫃 afterwards refers to a gong in a small cabinet; see this page for what I think might be an example.

篩面 means passing flour (面) through a sieve (篩), which would have also produced a tinny, metallic sound.

匣子 is a small box or a small case.

秤砣 means “steelyard weight,” which is an English term that I wasn’t familiar with at first. This is a weight that would be used in simple scales, and is sometimes known as a “Roman steelyard” or “Roman balance.” You can learn more about them here and here.

煞 here means “what,” and is a very informal, colloquial phrase. It’s the exact same as 啥 in modern Chinese. When you realize this, Granny Liu’s thoughts really stand out as being authentically rural.

陡 means abruptly or suddenly.

奶奶 here does not mean “grandmother” like it does in modern Chinese. Instead, it refers to the mistress, or the head ranking woman in the household. Here this is Wang Xifeng.

I'm not sure what it means, but I find it fascinating that it's exactly the kind of mental representation a farmer who’d never heard a clock might make, translating its sound into something familiar to her.