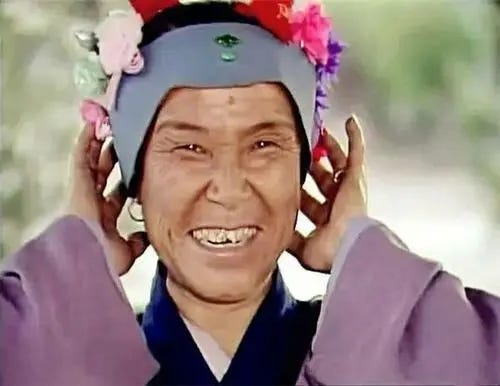

Granny Liu's Chinese

Granny Liu is one of the most interesting characters in all of Dream of the Red Chamber.

She, more than any other character, marks the author’s brilliance, as well as the depth of his understanding of Chinese. She speaks with a perfect rural Chinese accent, likely from somewhere in the northeast, and her phraseology and vulgarities and expressions are so authentic that they still feel right hundreds of years later.

Her language is also one of the most difficult things about this book to translate. I guess you could give her some sort of rural accent, but it just doesn’t feel right to me. We’ll see as the story moves along that David Hawkes does just that with Granny Liu’s colorful expressions. In my opinion, however, it actually detracts from the story.

We saw a few interesting examples yesterday of her blunt and somewhat vulgar speech. Here’s a good example:

咱們村莊人家兒,那一個不是老老實實守著多大碗兒吃多大的飯呢?

Don’t you see, the people here in our village, that there’s not one of us that isn’t used to being content to only eat as much as the size of our bowl?

In the Chinese, you can see that this is an excellent example of 反問, or a rhetorical question. Instead of coming straight out and saying something like, “you blockhead, you need to control your spending,” she uses a rhetorical question and a bit of rhetorical technique to soften the blow.

But then she turns really blunt:

如今所以有了錢就顧頭不顧尾,沒了錢就瞎生氣,成了什麼男子漢大丈夫了!

But now, the way that you’re spending money, you’re only thinking about today and not thinking about tomorrow. And when you’re out of money, all you can do is get angry over nothing. What kind of “real man” did you turn into?!

瞎 here is one of those great words that you’ll hear a lot if you’re in certain rural areas of northeast China, but that might confuse you if your Chinese study has been confined to books. It originally meant to be blind - and here you can think of 瞎生氣 as being in a blind rage if you want. 瞎說 (to speak nonsense) is the most common example, but rural northern Chinese uses 瞎 a lot more frequently than you’ll see in standard Mandarin. And young people to this day will say 瞎了!as a sort of curse.

Anyway, I’ll point out more examples of this as we come across them. Granny Liu’s Chinese is a stark contrast to the formal and high level Chinese of the likes of Lin Daiyu. It’s also amazing that a book as filled with great poetry as Dream of the Red Chamber would also have language that is utterly (and wonderfully) coarse and gutteral.