How To Translate Chinese Poems The Right Way

An extensive commentary on translating the untranslatable

How To Translate Chinese Poems The Right Way

Okay, I’m going to let you in on a little secret.

There is no right way to translate these old Chinese poems.

The problem is that you simply can’t do it. You’re not going to be able to keep the rhyme scheme intact. You won’t be able to get your readers to have the same emotional connection to the poem. You won’t be able to create the exact equivalent of that Chinese poem in English, or German, or French, or Japanese, or Korean, or any other language you try to translate it into.

That doesn’t mean that you should give up, of course. On the contrary: if you skip over the poems, like Pearl S. Buck did in All Men Are Brothers, her translation of 西遊記 (Journey to the West), you miss out on the flavor of the book entirely.

And, as bad as the constant poems are in 西遊記, the truth is that they’re even worse in 紅樓夢. At least Buck could write a somewhat coherent story without the poems! In our book, the poems are actually the point.

Now — if you’re a normal translator, translating day and night in preparation to publish a book, you’re stuck. You’ve got to come up with something, right? You can’t put every possible variation on paper. You can’t stick footnotes and endnotes everywhere. You need to figure something out, and you’ll absolutely wind up sacrificing important for the sake of readability.

If you think about this, you’ll understand why I’ve turned this project into a blog (well, technically a newsletter, but you know what I mean). Keeping this online, and creating a never-ending conversation between translator and reader, allows us to do things that we couldn’t do otherwise.

We’re going to look back at the poem we saw yesterday in this post. We’ll look at how others have translated it, and we’ll see if there are other ways to translate this poem.

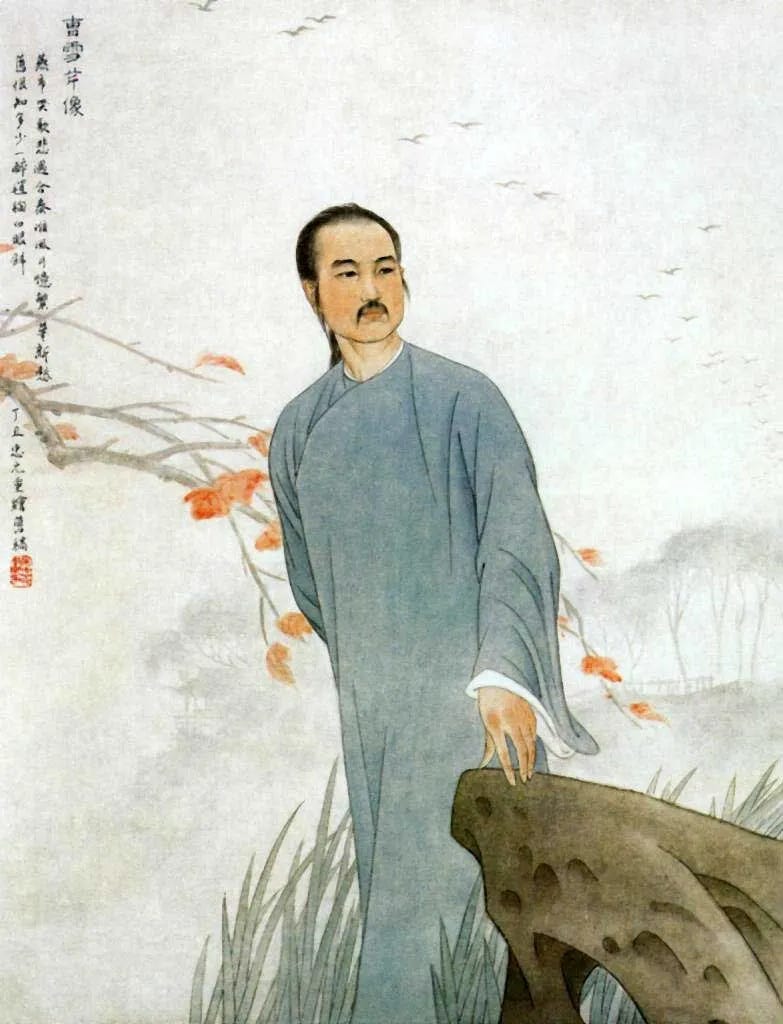

Don’t let your eyes gloss over. This might seem pointless and boring at the start — but, as we start digging into this book, you’ll realize that the poems really are the glue that holds the whole thing together. Cao Xueqin was a master poet, and the best way for those of us who unfortunately did not live with him and know him to understand his work is to turn to it time and time again.

First thing’s first. This is how today’s poem, the first “official” poem in 紅樓夢, was published in the 1792 程乙本:

Don’t worry if you can’t read it. We’ll figure it out together. Notice, though, that there are no punctuation marks at all. In fact, whoever owned this particular version of the novel didn’t even bother to write in the usual breath marks and pronunication notations that you usually see in older printed Chinese works.

It’s a pretty standard poem format: 7 characters per line, 4 lines in all. Now, if you want to get all geeky about it, you can call it a “quatrain,” which is the sort of big word professors like David Hawkes love to use. In Chinese it’s called a 七言絕句, a “seven character quatrain,” or 七絕 for short. And, of course, there’s a great Wikipedia article about the whole concept, where you can read examples from classical Chinese and Japanese poetry.

See why writing a blog is more effective?

Now, the problem with these poems is that they’re short. It’s hard to get a meaningful and understandable concept in when you’re limited to 28 characters. Fortunately for us, this particular poem is somewhat straightforward; we’ll get to some before long that are more difficult.

When we transcribe these poems today, we usually add in punctuation:

無才可去補蒼天,枉入紅塵若許年。此係身前身後事,請誰記去作奇傳?

But you don’t have to, actually. In fact, if you wrote it in the same format that they did back in 1792 (but going left to right, not top to bottom), it still is easy to read:

無才可去補蒼天 枉入紅塵若許年 此係身前身後事 請誰記去作奇傳

The reason why is that every single one of those 7 character lines forms an understandable concept. There’s no need to stick commas or question marks or periods or anything else in there. In fact, we can translate them one by one without worrying about the rest of the poem, and it kind of makes sense:

無才可去補蒼天

No ability to fix the azure heavens

枉入紅塵若許年

Vainly placed in the mortal world for years

此係身前身後事

This is the record of things before and after life (or “past and future life”)

請誰記去作奇傳

Please - won’t someone write it down and make a remarkable story

Now, when we take this poem back to the original context, things make sense.

Remember that we were just talking about the stone that the Goddess Nüwa didn’t have any use for. That helps us understand the first line. Although there is no stated subject (and there’s no room for one, since we’ve only got 28 characters to work with), it’s obvious from the context that this poem is about the stone.

The stone wasn’t good enough to fix the sky, and wound up in mortality wasting the years away. This record (in the context of the story, the inscriptions on the stone itself; for us, the entire book Dream of the Red Chamber) is the story of its life — won’t somebody please write it down?

That’s pretty similar to my translation:

No skill to mend the heavens above,

Long years lost in the mortal world.

This tale of its life, past and to come –

Who will record it, and pass it on?

Now, there are only a few ways you can possibly translate this poem — assuming that you’re going to stick to what the poem actually says in Chinese. We’ll soon encounter poems where this becomes a lot harder.

This is how Gladys Yang and her husband translated this poem in 1978:

Unfit to mend the azure sky,

I passed some years on earth to no avail;

My life in both worlds is recorded here;

Whom can I ask to pass on this romantic tale?

And here is how David Hawkes translated it in 1973:

Found unfit to repair the azure sky

Long years a foolish mortal man was I.

My life in both worlds on this stone is writ:

Pray who will copy out and publish it?

Now, the late Professor Hawkes was known for his expertise in Chinese poetry translation. He had a lot more practice at it than I have. I suppose that we could just go along with his translation and call it a day.

In fact, I’d argue that the Yangs did default to Hawkes. Their poem isn’t entirely the same, but it does seem to largely be a riff off Hawkes’ work. “Unfit to repair” turns into “unfit to mend;” “on this stone is writ” changes into the more natural “is recorded here,” and so on.

There will always be similarities, naturally. However, I strongly suspect that the Yangs consulted Hawkes on more than one occasion, especially for the formulation of these poems.

Now it’s time for fun.

I asked DeepSeek for a translation, and this is what it gave me:

No talent to repair the azure skies,

In vain to mortal dust so long confined.

This tale of past and present deeds supplies –

Pray, who will bear it hence for humankind?

This seems a little bit wordy and awkward to me. I’m also not entirely sure I understand what “supplies” is doing in the third line. However, “in vain to mortal dust so long confined” is a pretty powerful line.

I then asked ChatGPT for its opinion:

Lacking talent to mend the vast sky,

I have wandered in this red dust for so many years in vain.

These are but matters of life and death —

Who would remember them and turn them into a wondrous tale?

I really don’t like this poem, which is wordy and probably incorrect. “Red dust” here is an euphamism for the mortal world, and really needs to be translated that way. Similarly, 身前身後 cannot be translated to “life and death” to make any sense in this context. And, finally, GPT seems to not realize that 記 in the last line is better translated as “to record” (or, better yet, should be combined with 作奇傳 for something like “to bear a tale,” as DeepSeek does) than “to remember.”

I also asked ClaudeAI for its opinion:

With no talent to help mend the azure sky,

In vain I've entered the mortal world for so many years.

These are matters of my life before and after,

Who can I ask to record them as an extraordinary tale?

This is much better, though I still think DeepSeek does a better job at holding on to the feel of the original.

Finally, since we can be geeky and longwinded here, let’s take a look at a few other attempts to translate this into Asian languages that are a bit closer to Chinese.

We’ll look at Japanese first. I happen to have an electronic copy of 紅楼夢, though it only covers the first 80 chapters (more on that later) and doesn’t attribute the translation to anybody.

Anyway, this is the way that author translated this poem into Japanese:

わが才は蒼空を補修出来もせず、仕方なく浮世に入る幾年月、この身前身後に係わることを、誰にたのんで書き記して世に伝えよう

You’ll notice that I didn’t add in poetic lines. That’s because this is what the (apparently anonymous) translator decided to do:

Now, you can see some similarities here, right? “蒼空” is similar to “蒼天;” “補修” is similar to “補;” “身前身後” exists in both the Chinese and Japanese, and so on.

I’d translate the Japanese to something like this:

My talent cannot mend the azure skies, so, useless, I’ve wanderd the mortal world for years. These tales of life before and after death — who will I ask to write them down, to pass them on as legend?

Now, my Japanese is nowhere as good as my Chinese. However, thanks to the wonders of AI translation, I’d argue that this is a more appropriate rendition of this poem in Japanese:

才なくて 天を補えず

紅塵に 空しく年を重ね

これこそが 前世と来世の物語

誰が書きて 奇伝として伝えん?

What do you think?

Finally, I also happen to have a Korean translation. This is 홍루몽, published in 12 parts for some reason or other, translated by 안의운 and 김광렬. Here’s how they render this poem:

이 몸이 하늘을 받칠 재주가 없어

속세에서 헤매기를 몇몇 해이던고

전생 후생의 기구한 이 운명을

누구의 손을 빌어 세상에 전하리오

This is more poetic, and translates into:

This body lacked the talent to uphold the heavens,

And so wandered the mortal world for countless years.

This fate — strange, spanning past and future lives —

By whose hand will it be passed to the world?

The Korean translators also helpfully offer us the Chinese text right under their poem:

You’ll notice the variant reading here — 枘 instead of 請. I’m actually not sure if this is a legitimate variant from an early version of the novel, or if it’s a mistake — or even if it’s an encoding error in my copy. We’ll worry about that later.

And, since we did it for Japanese, let’s do it for Korean as well. Here’s an AI rendition of our Chinese poem:

하늘을 다듬을 재주 없어

헛되이 속세에 해만 흘렸네

이 몸 앞뒤 삶의 이야기

누가 적어 전설로 남겨줄까

I actually like this better than the translated version. It’s more accurate: for example, “하늘을 다듬을 재주 없어,” “no skill to mend the heavens,” is a much more accurate rendition than “하늘을 받칠 재주가 없어,” “lacking the talent to uphold the heavens.” It’s also more succinct: “누가 적어 전설로 남겨줄까,” or “who will write it down to leave it as a legend” is shorter and more accurate than “누구의 손을 빌어 세상에 전하리오,” “by whose hand will it be passed on to the world.”

But, honestly, I’m just nitpicking here. The best thing that the Korean authors did was to include the original in 한자 (the Korean equivalent of Chinese characters) for students to dig into.

So what? So what did we learn about the “right way” to translate Chinese poetry?

You’ve got to keep it readable. David Hawkes gets a lot of praise for his poems — but the truth is that nobody reads them. His beautiful language is archaic, and is becoming increasingly unreadable. You’ve got to know your audience and speak to them. In my opinion, “the azure sky” might have been readily understandable in 19th century England, but most people today won’t know what you’re talking about.

You’ve got to keep it a poem. I know the Japanese translator worked hard, but that simply is not a poem. You’ve got to keep the poems structured as poems.

Don’t worry about rhyming. Hawkes loved to rhyme. I personally don’t care if the poem rhymes or not. Chinese poetic “rhyming” structure was more tonal based than anything else, and we’re simply not going to recreate it in English.

Sense is better than form. It’s not a huge issue here, but we’ll need to keep this in mind as we move to the more difficult poems. The most important thing is that your reader can figure out what’s going on. In fact, we’ve got a poem coming up eventually that will demonstrate just how important it is to emphasize sense and understanding over rhyming scheme and form.

Am I crazy? Do you like this? Do you hate it? Please leave a comment to let me know!

Glad to see that you checked with DS and GPT, which I did as well. The poem was too well known, so when I input it the AIs recognised it immediately as from 红楼梦, and whatever translation they did weren't purely off the actual text, but highly influenced by the existing translation by Hawkes and the Yangs.

I gotta laugh at this: "David Hawkes gets a lot of praise for his poems — but the truth is that nobody reads them. His beautiful language is archaic, and is becoming increasingly unreadable." I don't disagree, so far.

Correction: Pearl S. Buck's All Men Are Brothers was a translation of 水滸傳 (Water Margin), not 西遊記 (Journey to the West)