Melancholy In Paradise

Wang Xifeng ends her brief discussion with Qin Keqing. This passage ends with an absolutely gorgeous poem. Honestly, this is one of the most beautiful and descriptive literary passages we’ve encountered so far in this novel. More on that tomorrow.

My Translation

After Baoyu left, Wang Xifeng stayed for a while longer. She urged Qin Keqing on and told her a number of earnest words from the bottom of her heart. She stayed for so long that Lady You wound up sending servants over a few times to try to get her to leave.

“Rest well and get better,” Xifeng said to Qin Keqing at last. “I’ll come back to see you soon. Your sickness should be getting better, especially since you were able to meet with that good doctor the other day. There’s nothing to worry about anymore.”

“Even if he were a God, he could only cure my disease, but not my fate!” replied Keqing with a faint smile. “Aunt, I know that I can only take life one day at a time with this illness.”

“How can you ever get better if you keep thinking that way?” said Xifeng. “You really need to be more positive. Besides, I heard the Doctor say ‘If the disease is left untreated, things will be really bad in the spring.’

“If we were so poor that we couldn’t afford ginseng, we’d have no chance. But your in-laws would buy you pounds of ginseng a day if they thought it could cure you. Rest well and build up your strength. I’ve got to go back through the garden now.”

“Dear Aunt,” replied Keqing, “please forgive me for not being able to go with you. When you have a moment, please come over and see me again. We can sit for a while a have a nice talk together, just the two of us.”

Xifeng’s eyes started watering when she heard that. “As soon as I have some free time, I’ll come back to see you,” she promised. And with that she went out through the inner rooms to a side gate leading into the garden, accompanied by the maids she had brought along with her.

When she left, she saw

Golden blossoms covering the ground,

Pale willows sweeping the slopes.

A small bridge covers a stream like Ruoye,

A winding path leads to a hill like Tiantai.

The stream trickles in through the rocks,

And sweet smells come through the bamboo fence.

Red leaves dance on top of the trees,

And the woodland looks like a painting.

The western wind blows suddenly,

Yet you can still hear the orioles sing.

The warm sun lingers,

And the cricket songs join the chorus.

Looking to the distant southeast,

You can see several buildings nestled in the hills.

Looking to the near northwest,

You can see three open halls over the water.

Wind instruments swell the seats with sound,

Awakening profound emotions.

People in expensive silks tread through the woods,

Only adding to the beauty of the scene.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

Hawkes translates 若耶之溪 (the Ruoye Stream) as “a storied stream,” with no discussion of the literary implications. It’s kind of unfortunate, since it’s not clear to the reader why this stream would be “storied.” This is actually a literary allusion that winds up lost in the translation.

Hawkes translates 天台之路 (the path to Tiantai) as “a fairy hill,” which is also not entirely accurate. 天台 (Tiantai) has clear implications as a mountain special to certain Buddhist believers, and is also associated with Chinese mythology. Again, this is a clear literary allusion that has been lost in the translation.

Probably the strangest part about the Hawkes translation is that he renders 疏林如畫 as “a wintry copse described calligraphic traceries.” A copse is a thicket of small trees or a woodland. But it’s absolutely clear that the original says “the woodland looks like a painting.” I believe Hawkes wanted to rhyme “traceries” with “fragrances,” though it’s really a false rhyme. At any rate, his translation here takes an otherwise simple description and makes it hopelessly complex.

Hawkes translates 幽情 as “melancholy,” which is absolutely appropriate given the context.

Yang

The Yangs add this bit into Wang Xifeng’s attempts to console Qin Keqing:

It’s only the middle of the ninth month now. You’ve four or five months yet, quite long enough to recover from any illness.

This is not in the 1792 version of the novel; I’m not sure if it shows up in an earlier manuscript, though I’d honestly be surprised if it did. It seems that they were emphasizing the fact that Wang Xifeng was still optimistic about Qin Keqing’s long term outlook.

The Yangs completely miss the literary allusions. 若耶之溪 turns into “the brooks” and 天台之路 is rendered as “quiet retreats.” Any reader entirely reliant on this translation would have no idea that there’s deep literary allusion in this poem.

The Yangs also translate 疏林如畫 as “in scattered copses lovely as a painting,” which betrays the clear influence of David Hawkes’ translation. Remember that the first volume of The Story of the Stone had already been published by the time the Yangs published their entire work. I seriously doubt they would decide to use an unusual word like copse to translate a simple concept like “woodland” if they hadn’t been influenced by the existing translation.

The Yangs translate 笙簧盈座,別有幽情 as “Fluting cast a subtle enchantment over men’s senses.” This is also confusing, especially the word “fluting.” What the original actually says is that the sound of wind instruments cover all of the seats (perhaps the audience for a Chinese opera performance?), awakening a separate feeling of deep melancholy among the listeners. “Subtle enchantment” is inappropriate given the overall somber mood of the scene.

I honestly think the Yangs struggled to understand what this poem meant. It’s supposed to be a reflection of Wang Xifeng’s deep worry among the beauty and magic of the garden scene. Their translation seems to focus only on the magical nature of the garden, completely missing Wang Xifeng’s pensive and depressed mood.

Chinese Text

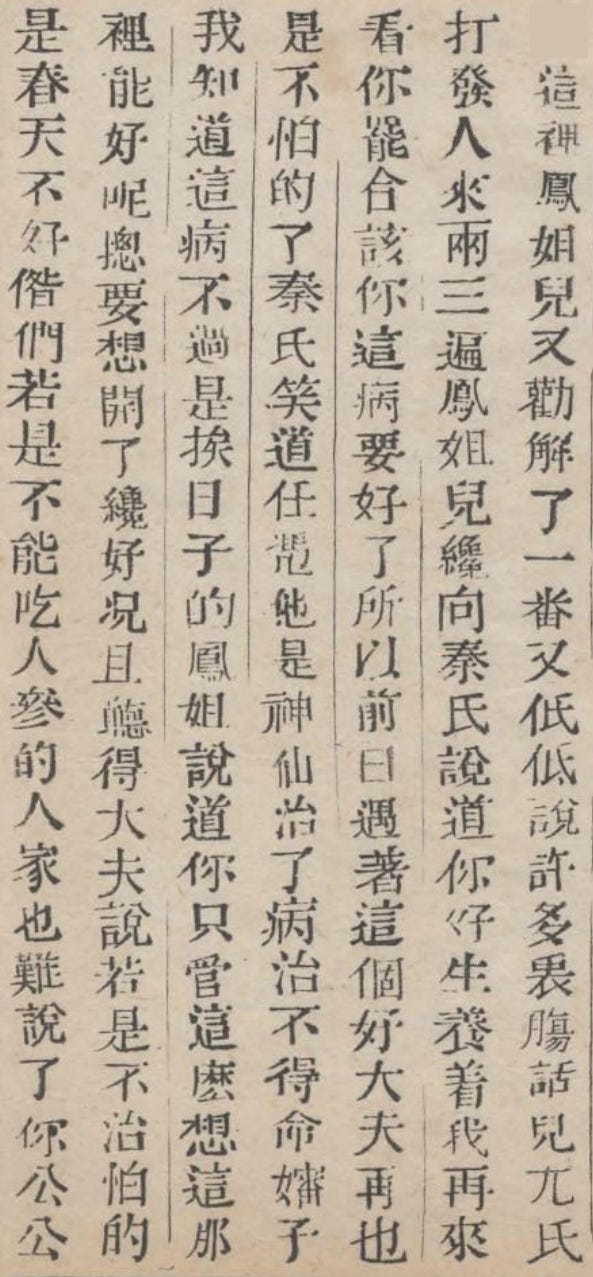

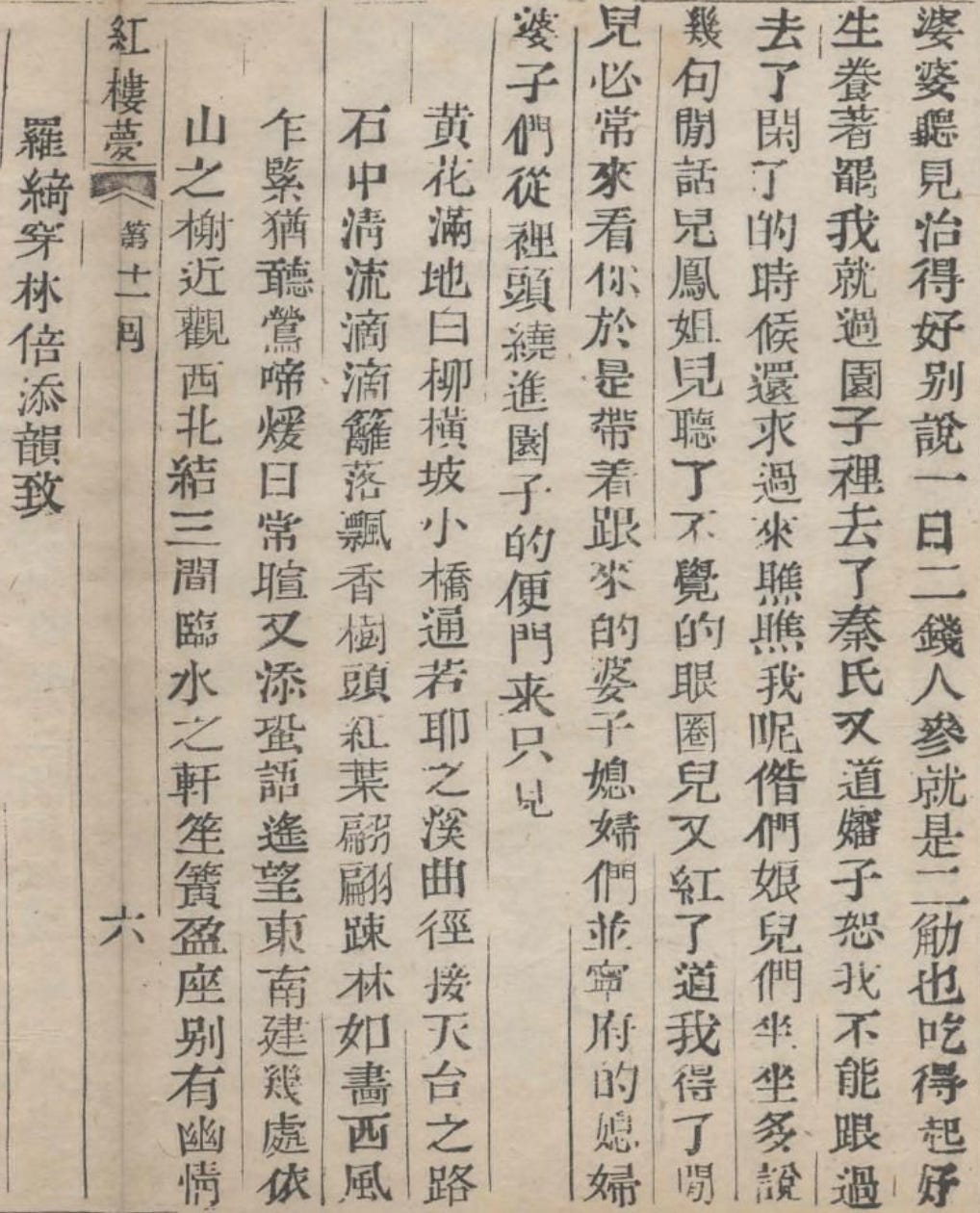

這裡鳳姐兒又勸解了一番,又低低說許多衷腸話兒。尤氏打發人來兩三遍,鳳姐兒才向秦氏說道:「你好生養著,我再來看你罷。合該你這病要好了,所以前日遇著這個好大夫,再也是不怕的了。」秦氏笑道:「任憑他是神仙,治了病治不得命!嬸子,我知道,這病不過是捱日子的!」鳳姐說道:「你只管這麼想,這那裡能好呢?總要想開了才好。況且聽得大夫說:『若是不治,怕的是春天不好。』咱們若是不能吃人蔘的人家,也難說了;你公公婆婆聽見治得好,別說一日二錢人蔘,就是二斤也吃得起。好生養著罷,我就過園子裡去了。」秦氏又道:「嬸子,恕我不能跟過去了。閒了的時候,還求過來瞧瞧我呢,咱們娘兒們坐坐,多說幾句閒話兒。」

鳳姐兒聽了,不覺的眼圈兒又紅了,道:「我得了閒兒,必常來看你。」於是帶著跟來的婆子媳婦們並寧府的媳婦婆子們,從裡頭繞進園子的便門來。只見:

黃花滿地,白柳橫坡。小橋通若耶之溪,曲徑接天台之路。石中清流滴滴,籬落飄香;樹頭紅葉翩翩,疏林如畫。西風乍緊,猶聽鶯啼;暖日常暄,又添蛩語。遙望東南,建幾處依山之榭;近觀西北,結三間臨水之軒。笙簧盈座,別有幽情;羅綺穿林,倍添韻致。

Translation Notes

衷腸 means words earnestly spoken from the bottom of one’s heart. This is going back to the more tender and emotional version of Wang Xifeng that we saw a few passages ago.

合該 means “should” or “ought to” and is an auxiliary verb; in other words, it is kind of a helping verb.

捱日子 means to endure each day one at a time

若耶之溪 refers to the Ruoye Stream (occasionally shorted to 若耶溪). It’s a small river in Shaoxing City in Zhejiang Province, and is associated with numerous Chinese legends. This small river has been the focus of poetry through the ages, particularly in the Tang dynasty. See the Chinese Wikipedia entry for more.

天台之路 refers to the path leading to Tiantai Mountain in Zhejiang province. This mountain was supposedly the place where the mythical goddess Nüwa cut the legs off a giant sea turtle to use them to prop up the sky. Mount Tiantai has been a historic destination for Buddhist pilgrims for over a millenium.

籬落 is a bamboo fence.

乍 means suddenly

別有幽情 is the sort of phrase that will keep me up at night. 情 is a word that we see all the time in this book: it means more than “passion” and is probably something more like “emotion.” 幽 can mean something hidden or secret, or even something that has been bottled up. When combined, 幽情 usually means a pensive mood. However, given the way Wang Xifeng feels about her best friend passing away, it probably means something more like “profound emotion” or even “profound sorrow.” The hard part, though, is 別有, which literally means “this exists separate from everything else.” I’ve chosen to associate it with the playing of music, which I believe is what the other translators of Dream of the Red Chamber have also chosen to do.