My Language Learning Secret

How to learn how to read Dream of the Red Chamber in the original

My Language Learning Secret

The big secret is that you can learn how to read a book like 紅樓夢 yourself. It’s not as hard as you think.

I know, I know. There are a ton of different websites and companies out there trying to sell you foolproof language learning methods. The most popular selling point is some variation of “it’s easy,” or “you can learn naturally.”

I strongly disagree that any aspect of foreign language study can be considered easy. However, when you understand how humans tend to learn languages, and when you start learning how to use different tools to take advantage of your natural learning capacity, a dream that once seemed impossible now becomes possible.

So let’s get into it.

I’m going to assume that you want to learn how to read a book like Dream of the Red Chamber in its original pre-contemporary Chinese. This book requires some dexterity with classical Chinese as well as a good foundation in modern Chinese. However, it is doable, even if you’re still a beginner to the Chinese language.

If you’re interested in learning a different language, don’t worry. These basic rules still apply.

How To Begin

The hardest part of learning a foreign language is to figure out how to begin.

Fortunately, the hard part is mostly over. You can easily find material on YouTube designed for beginning students in any language you can think of.

Your goals in the early days are simple. You want to learn the sounds of the language, learn a few beginning sentences, and get yourself off to as solid a foundation as you can.

When I learn new languages, I tend to look for introductory level textbooks that include CDs or audio files. You need to remember that you’re not going to be able to learn any language just by looking at the words on a page. It’s important to master the skills of speaking and listening in addition to reading and writing — even if your ultimate goal is to just read something. In other words, somebody who actually learns how to speak modern Hebrew or modern Greek will likely find the ancient forms of those languages far less daunting than somebody who only learns the theory on paper.

Once you’ve gotten a feel for the language, some of the grammar, and other beginning steps, we can get into the tricks.

Spaced Repetition Software

When I started learning Chinese 20 years ago, I made a bunch of small vocab cards by hand.

It was a laborious process. I’d take a bunch of index cards, cut them up in quarters, and would write Chinese on one side and English on the back. I’d go through each of the cards several times a day, and would do a new set every week.

Once I was done with a set, it was back to the drawing board. I never knew what to do with the cards I had just finished. I also had a number of issues with general recollection, and caught myself making the same cards over and over again after a little while.

The best way to burst out of this karmic cycle is to use spaced repetition software.

My advice is to go straight for Anki.

Anki is free, customizable, and is quite versatile. While there is a little bit of a learning curve, once you understand how the program works and how you can customize it, it will save you hours upon hours of time.

If you treat Anki’s algorithm seriously (that is, if you don’t cheat), you’ll find that it has a tendency to show you a card right before you’re about to forget it. In other words, the old problem of accidentally relearning the same words over and over again is now gone.

The best thing about Anki, by the way, is that we can create flashcards with more than two sides. This is kind of hard to understand intuitively — so let’s work through an example together.

Making The Most Of Anki Notes

First of all, there’s a difference between “notes” and “cards” in Anki.

A “note” is basically a collection of information about a certain vocabulary word. You can have a ton of fields in a note if you like.

A “card” is how a note is represented to you when you study it. You can have an infinite number of cards connected to a single note.

By default, Anki “Notes” give you two “cards” — one that shows you the “front side” first and has you guess the back, and one that goes the other way around.

It’s the same as the language cards I created decades ago. You write the target language on one side and your language on the back, and then work through them until you’ve connected the two in your mind.

However, Anki is different. It allows you to create an unlimited number of “cards” for each “note.” Or, in other words, a single Chinese word can be learned from a number of different perspectives.

This is powerful. This allows us to make the most of learning reading, speaking, writing, and listening. In fact, we can approach a single Chinese word from multiple different angles, learning it to a degree that we never could achieve with those homemade scraps of paper.

But enough abstract talk. Let’s see this in action.

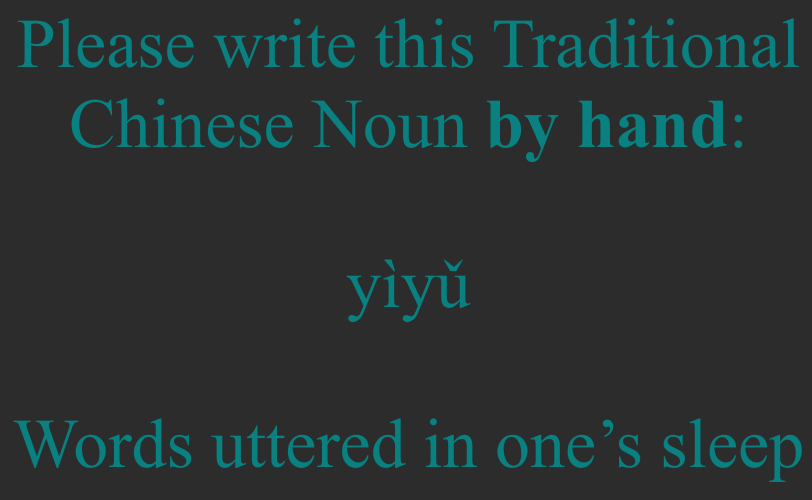

This is a Chinese note I made a few years back:

This is the word 囈語, or yìyǔ in Pinyin. It means “words uttered in one’s sleep,” and can also refer to babbling or nonsensical language.

It’s not common at all, by the way. People don’t walk down the street in China muttering about 囈語. Most of your Chinese friends probably wouldn’t know how to write this word if you quizzed them, though my guess is that just about all of them would know how to pronounce it if they saw the characters.

Now, the default Anki card would have 囈語 on the front and “Words uttered in one’s sleep” on the back. But we’re going to go further than this. We want to make cards that cover reading, writing, speaking, and listening.

And, more than that, we want to make sure that every single card asks us to do only one thing. You don’t want a bunch of cards that ask you to perform a ton of tasks. You want a single card to ask you to do a single thing. If you want to learn more than one thing about a card, make more than one card.

Speaking

First, we want to learn how to read 囈語 aloud. That way, when it comes up in one of our older Chinese novels, we won’t have to rush to the dictionary and frantically thumb through to figure out what in the world is going on.

This is pretty easy to do. We’ll make a card that asks us to read 囈語 aloud.

I created a bunch of reading cards that ask me to read the word. I make sure to give myself everything but the pronunciation so that I’m not asking myself what this word means. In this case, my card looks like this:

When I turn the card to the back, I get the Pinyin, as well as a recording of a voice reading 囈語:

For individual vocabulary words, I recommend looking on Forvo for native speaker readings. If you can’t find it there, I strongly recommend looking into a tool like HyperTTS, which is worth every penny.

Now, it just so happens that there is a simplified Chinese version of 囈語 as well:

I have each note set up to automatically create new cards for words that have variant simplified Chinese readings. That way, when I import a vocabulary list into Anki, I don’t have to spend time creating new cards by hand. The pronunciation of 呓语 is the same file as the pronunciation of 囈語, since they are the same word.

Writing

It’s not enough to learn how to read a note. In fact, if you don’t know how to write in Chinese, you’re never going to make enough reading progress to get to the point you want to be.

As a result, I’ve created writing notes for all my Chinese vocabulary cards. I’ve also done the same for my cards in Korean, Japanese, Cantonese, Taiwanese Hokkien, and similar languages.

When I study Anki every morning, I make sure I’ve got some writing paper handy. When I was in China 20 years ago, I bought a small Chinese character notebook to practice in — the sort of thing Chinese kids use when they’re learning how to write. Practicing writing this way was so helpful that I made a scan of one of the pages. These days I print off hundreds of copies of that scanned page and use it for my writing practice.

The writing note for 囈語 looks like this:

The sound file plays automatically once this card comes up.

I’ll write the word once and will then flip the card over to the backside, which looks like this:

If I got it right, I’ll write 囈語 for two full lines and will mark the card as correct. If I was wrong, I’ll write for two full lines, mark the card as wrong, and will practice it again.

I’ve also got this set up for simplified Chinese writing practice:

In my experience, the most important part of learning to read these languages is learning to write them by hand. There is no substitute for how writing by hand can internalize the shape and innate nature of these characters. The more you write, the more the language becomes part of you.

Reading

We also want to make sure that we know what 囈語 means when we see it. This is similar to reading it aloud, except this time we want to test ourselves for its meaning, not pronunciation. This is how I have it set up:

The sound file plays when the character is shown. This means that all I have to worry about is what it means.

This is what the back looks like:

And, again, we can do the same thing with simplified Chinese.

Listening

Finally, we get to listening.

There are two ways to handle this. The first is to simply know what a word is by hearing it:

All of my vocabulary listening cards look like this. I hear the voice and have to know what word it is.

The back looks like this:

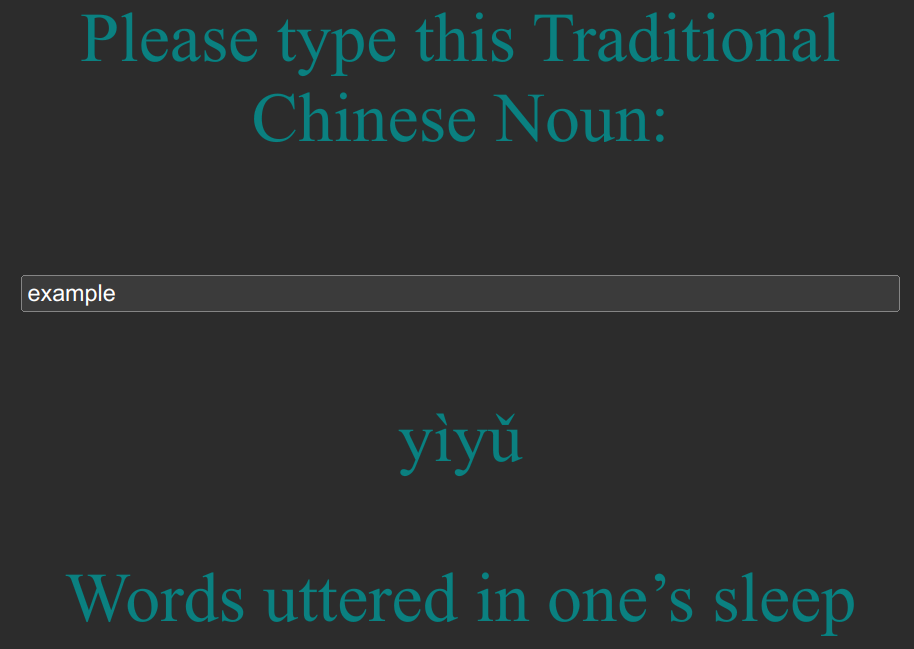

The second way to handle listening (and, by extension, writing) is to create a “dictation” card. This is a bit trickier to set up in Anki, but, once you’ve got it figured out, it can help you a lot with typing and with character recognition.

In this kind of card, 囈語 is read out to me, and I have to be able to type it in a box that pops up:

Anki will automatically tell me if I wrote the word correctly or incorrectly.

How To Set This Up

Sounds good, right? But how do you set this up?

First thing’s first. You’ve got to set up your notes right. You need to have all the right information in them.

This is the note I’ve created for 囈語:

You’ll notice that this is different than most of the notes you’ll see saved on AnkiWeb. There’s a lot of information I could have here that I don’t.

I know I’m going to want to learn both traditional and simplified Chinese, so I’ve got a field for both. I know I’ll need the Pinyin as well. I like having the grammatical category, I’ll need a definition, I like having the sound file, and it’s a lot easier to keep things straight if you’ve got a Language field, especially if you’re going through cards in a dozen or so languages.

Now, the cards themselves are a little tricky, but they’re not so hard when you get used to the programming language. For example, a “Speaking” card looks like this:

Please read this {{Language}} {{Grammar}}:<br><br>

<div style='font-family: HanaMinA; font-size: 40px;'>{{Chinese}}</div><br>

{{Definition}}

Now, you don’t need the font definition if you don’t want it. I’m using HanaMinA largely to account for the rare characters that I tend to run into when I study Cantonese and Taiwanese Hokkien.

This is what the back looks like:

{{FrontSide}}

<hr id=answer>

<div style='font-family: Times New Roman; font-size: 30px;'>{{Sound}}</div>

{{Pinyin}}<br>

Most of the other cards are variations on that rather simple format. In fact, the only really tricky one is the dictation card, which looks like this:

Please type this {{#Simplified}}Traditional {{/Simplified}}{{Language}} {{Grammar}}:<br><br>

{{Sound}}

{{type:Chinese}}

<br>

{{Pinyin}}<br><br>

{{Definition}}

The “{{type:Chinese}}” instruction is the field that lets the input box pop up.

Also — the “{{#Simplified}} … {{/Simplified}}” instruction tells Anki to only include that word if there actually is something in the Simplified field. If a card only has a Traditional field (i.e. the simplified Chinese version is the same as traditional Chinese), Anki skips over this automatically.

You can use that for entire cards, by the way. My simplified dictation card looks like this:

{{#Simplified}}

Please write this Simplified {{Language}} {{Grammar}} <b>by hand</b>:<br>

{{Sound}}<br>

{{Pinyin}}<br><br>

{{Definition}}

{{/Simplified}}

That’s pretty much it. There’s nothing more difficult to it than any of this. In fact, the hardest part of this was figuring out how to set it up.

Using Sentences To Learn Context

Now comes the fun part.

Learning individual vocabulary words is simply not enough. You need to learn sentences and phrases to learn what things mean in context.

A lot of people will tell you to learn the target language in the target language. That’s kind of a paradoxical statement when you think about it. How in the world are you going to learn something by using something you don’t know yet?

The truth, however, is that all languages require you to understand the context in order to get the meaning.

The best way to learn this stuff is to simply expose yourself to as many sentences and phrases as you possibly can. And, of course, that means reading a ton, watching television in the target language, and spending time extracting audio from your sources and sticking them in Anki.

I’m not going to go into too much detail about where to find sources for this kind of material. I’m also not going to go into too much detail on using Audacity to export audio and that sort of thing. I recommend looking up how to use AI tools like Whisper for media for which there is no script or subtitles, and then messing around a bit to figure out what workflow works best for you.

Now, we can do this with sentences from any source we might happen to have. Let’s say that you’re interested in a particularly moving sentence from Dream of the Red Chamber, for example. I made notes a few years back featuring various sentences from the start of the novel. Here’s one:

Again, you can see here that I’m only asking myself to do a single thing when this card pops up. All I want to do is have myself read the characters. I’m not worried about the meaning at all.

The back part of the card has a voice reading the sentence aloud. This voice comes from a professional recording of 紅樓夢 that I’ve included for paying subscribers in the files section.

I’ve also got a card connected with this note that asks me to state the meaning of the sentence:

And then there’s one just asking me to listen to the sentence and say what it means:

This can be useful if you want to know what something like 儀容 or 不俗 means in context. Sometimes these vocabulary words can be a lot easier to remember when you see them over and over again in actual sentences.

I do this in every language I learn with sentences and phrases. In fact, I tend to spend more time learning setences and phrases than I do learning normal vocabulary. This part of language learning is quite addicting, and you can get a lot done in a short amount of time — especially when you get the hang of Audacity, Whisper, and a few other useful tools.

Mastering Grammar

And now we come to the big part: mastering grammar.

It’s important to learn gramar, and you shouldn’t skip out on grammar books. However, when you get a grammar book, you want to get a book that has as many example sentences as possible. I’ll show you why.

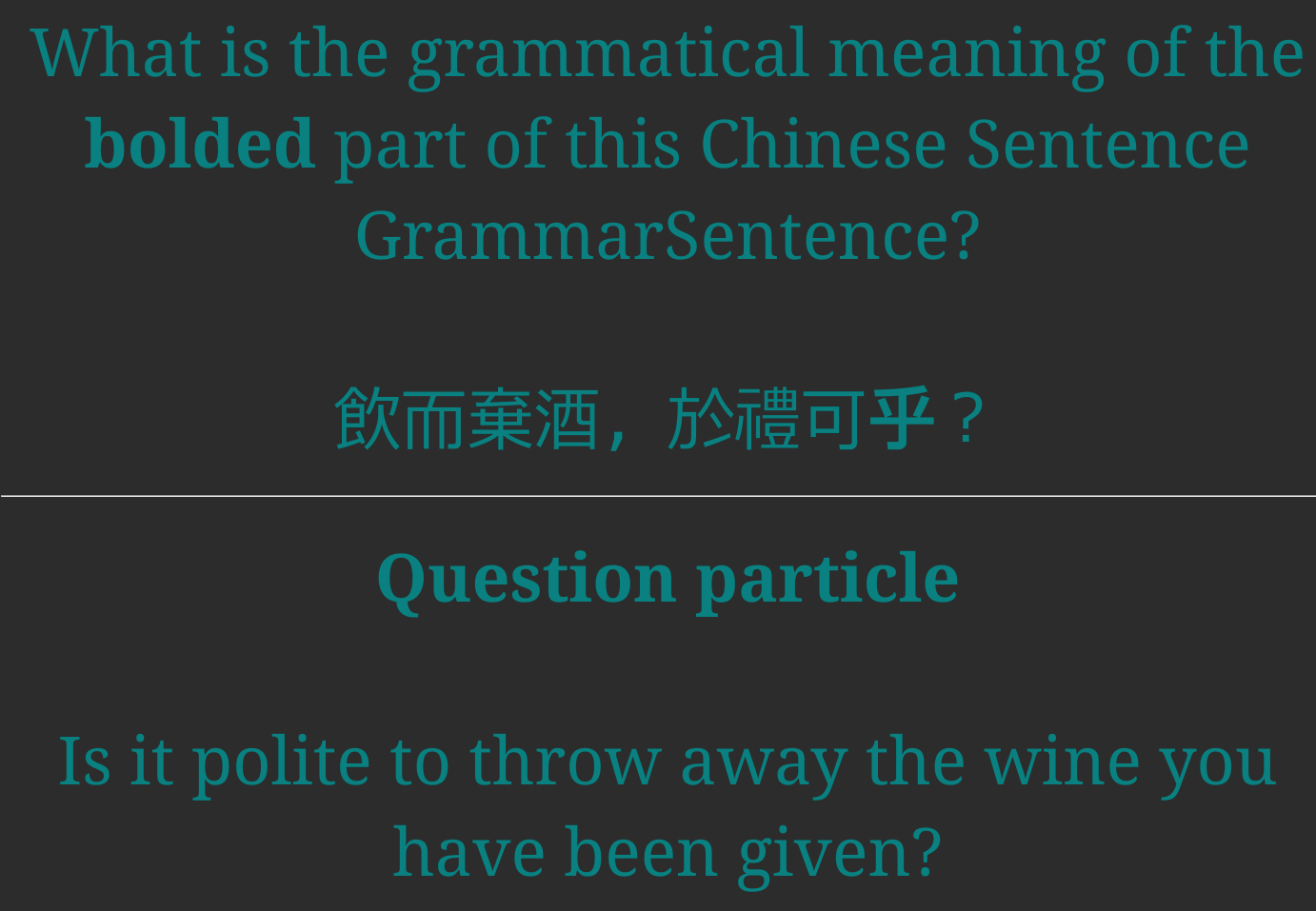

Classical Chinese grammar can be difficult because the same grammatical particle will mean different things depending on where it is in the sentence. There’s no easy way to memorize this.

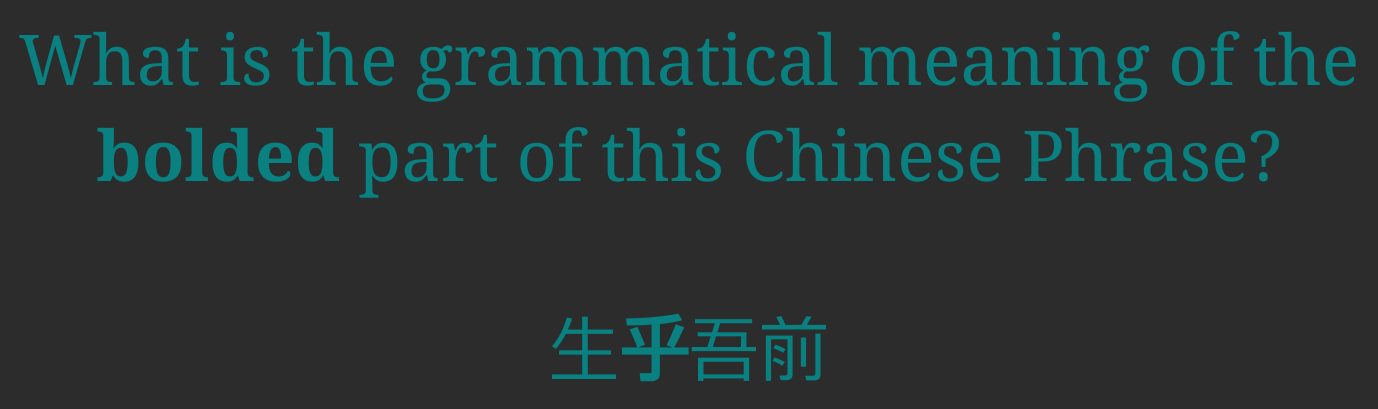

For example, in the sentence 飲而棄酒,於禮可乎?, the ending particle 乎 is a question particle, similar to 嗎 in modern Chinese. However, in the phrase 生乎吾前, 乎 means “at” or “on,” similar to 於 (or 在 in modern Chinese).

Now, you’re not going to get very far with a vocab card for 乎 that lists 8 or 10 definitions. You need to learn that grammatical concept through context.

And so I created a certain type of grammatical note for Chinese. The first sentence looks something like this:

When I create these cards, I make sure to write in HTML code for the bolded part of the sentence. This is easy: just add in <b> before the part you want to bold and put in </b> when you’re done.

On the back I have both the grammatical use and the meaning:

In retrospect, I probably should put the definition on the front of the card to simplify the process for myself. The important thing here is not what the sentence means, but, rather, what the grammatical partical means.

It’s then easy to learn the difference in the various forms of 乎. That card is completely different from this one:

Learning grammar in context quite literally is a cheat code for learning a foreign language. In fact, if you combine this with watching television and movies using the target language, as well as a lot of reading, you’ll discover that you’re able to learn and hold onto even the most obscure grammatical readings for much longer than you will with any other method.

And, as I said before, this can be used with any language. Want to learn ancient Greek declensions? Go for this method.

Preparing New Notes

Finally, a brief word on preparing new notes.

Anki is easy. You can import notes from a spreadsheet, provided that the spreadsheet was saved in CSV format.

All you need to remember is that you need one line for every field in your note. My current Chinese spreadsheet looks like this:

I’ve got different note types for “Chinese” and “Chinese sentences.” In other words, when I’m ready to upload things into my Anki decks, I’ll edit this spreadsheet, separate out the sentences and phrases, and will stick those in their own spreadsheet. That way Anki doesn’t ask me to write an entire sentence by hand.

I strongly recommend ditching Microsoft Excel and using LibreOffice Calc instead. In fact, if you’re going to upload a CSV file to Anki, you must use LibreOffice Calc to save your spreadsheet into the CSV format. Excel does wonky things if you try to do it that way.

Doing this is much easier and faster than trying to create a new card for each new vocabulary word. I usually stick things in my decks once a month and let the algorithm do its thing.

Am I missing any steps? Is this helpful? Let me know in the comments!