The English Translations

A look at the various translations of Dream of the Red Chamber — and why I don't like any of them

The English Translations

I’ll be honest. I’m nervous.

I’m worried that I’ll translate something incorrectly. I’m worried that I’ll miss some obvious connection to some important thing in Chinese history or classical Chinese culture that is obvious to everyone. I’m worried that I’ll just make a fool out of myself.

However, when I compare my work to the work of those much smarter and much more talented than me that have gone before me, I kind of feel better.

The truth is that there really is not a good translation of 紅樓夢 in English. There’s not. The two major translations that everybody uses are pretty bad. There are a number of minor translations as well, each of which suffers from its own problem.

I know. I own far too many versions of this book.

Let’s get into it.

The Story of the Stone by David Hawkes and John Minford

This is the classic version that most people think of as the “official” English translation.

It came out in 5 volumes, and I believe was originally published by Penguin. Volume 1 was published in 1973; Volume 5, on the other hand, didn’t come out until 1986.

The story behind this is that David Hawkes ceased teaching at Oxford sometime in the late 1960s to focus his attention on 紅樓夢. He wound up with a contract with Penguin Books to come out with what Wikipedia calls a “non-scholarly” edition of the book.

My understanding was that Hawkes took 10 years to translate it, though it seems that it took more like 16 or 17 years. In part because of the grand scope of this translation, it has been adopted as a sort of “canon” translation in the academic community. To my knowledge, all English language academic works dealing with Dream of the Red Chamber use the Hawkes/Minford translation as their base text.

If you’ve been reading along with me so far, you know that there are a number of problems with the Hawkes translation. These include:

A complete lack of footnotes. I know that this was intended for the “lay” reader, but Hawkes really needs to explain some of the terms that he’s using to his poor English speaking audience, which is coming to this book with little to no cultural context.

The incessant use of foreign words and phrases. This annoying practice ranges from transliterating Chinese words to combining Sanskrit adjectives with Latin names, and only gets worse as the text proceeds. The worst part is when Hawkes translates lines from Confucius into Latin.

The fact that he didn’t translate the whole book. Nobody seems to notice that Hawkes missed the first paragraph. While he did translate some of it in the introduction, he missed the bit about “dreams” and “illusions” that forms the core of the novel. As I’ve shown so far, you can find evidence scattered throughout the translation that Hawkes struggled to understand some of the core philosophic issues addressed in this novel.

The long and windy sentences. Hawkes tried to translate 紅樓夢 into a 19th century English novel. As a result, short and quick sentences in Chinese tend to be rendered into long and boring prose — almost certainly the reason why hardly anybody has read Dream of the Red Chamber outside China.

The lack of a base text. Hawkes decided not to translate either the 1791 or 1792 officially published texts. Instead, it seems that his translation was formed by combining what he thought the most interesting parts were from the various existing manuscripts. The result is an absolute mess that few scholars have even tried to address.

The biggest problem is that the Hawkes translation has served as the basis of countless foreign translations. Many translators simply assume that Hawkes created the best translation and don’t bother to go to the Chinese original.

Professor Fan Shengyu released a bilingual Chinese-English version of the Hawkes translation in 2014:

This version was published in Shanghai, and is extremely difficult to find outside China.

A Dream of Red Mansions by Gladys Yang and Yang Hsien-Yi

For years, this version was the only version you could find in the People’s Republic of China.

American Gladys Yang and her husband, Yang Hsien-Yi, spent years working on this translation in China. Their work intersected with the horrors of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. In fact, they spent some time in prison, though their incarceration apparently did not significantly delay their translation.

Their version was published in 1978.

It’s not an awful translation, though parts of it show a lot of influence from the Hawkes translation — especially the early chapters that Hawkes had already published by 1978.

Issues include:

Paraphrasing instead of translating. The Yangs were pretty fond of punting the ball when they found themselves in a tight spot. We’ve seen that already in a few places.

Using plain language. The Hawkes translation is dazzling in its use of English and in its excellent poetry. The Yang translation, on the other hand, feels a lot more simple and plain.

Missing important textual points. While the Yangs are good at pointing things out in their footnotes, there are other times in which they completely miss the nuance of a sentence.

Marxist interpolations. The Yangs stick a number of Marxist interpolations into their work. This might be in part because of the state of literary culture surrounding Dream of the Red Chamber in China in 1978.

I once thought that the Yang translation was more “literal” than the Hawkes translation, but now know this is not the case. If you rely solely on the Yang translation you’ll end up missing a lot of the richness of the novel, and much of its symbolism will be totally lost on you.

Other Translations

There are a few other translations worth noting.

Red Tower Dream: The Tale of a Rock by Eugene Ying and Victor Ying

This appears to be a machine translation version created by two engineers, who apparently have translated all of the Chinese classics.

I initially wanted to use this translation for textual comparisons, but decided not to after I started reading it. Sadly, Eugene and Victor Ying don’t understand how tense works in English. The translation constantly shifts between the present and past tense, creating an unreadable mess.

They tried translating names to English words, but with strange results. Jia Baoyu, for example, becomes “Jade,” which, of course, is a girl’s name.

Stay away from this translation. In fact, you might want to think twice before you buy any of the translations from these guys. I smell a scam.

Dream of the Red Chamber by Emma Reynolds

This version is a scam. Reynolds apparently put the entire Chinese text into something like ChatGPT, which spat out a version eerily similar to the Hawkes translation. A few synonyms for some of the English words Hawkes used were substituted in by somebody or other. It’s a garbage translation that honestly should be removed from Amazon for fraud.

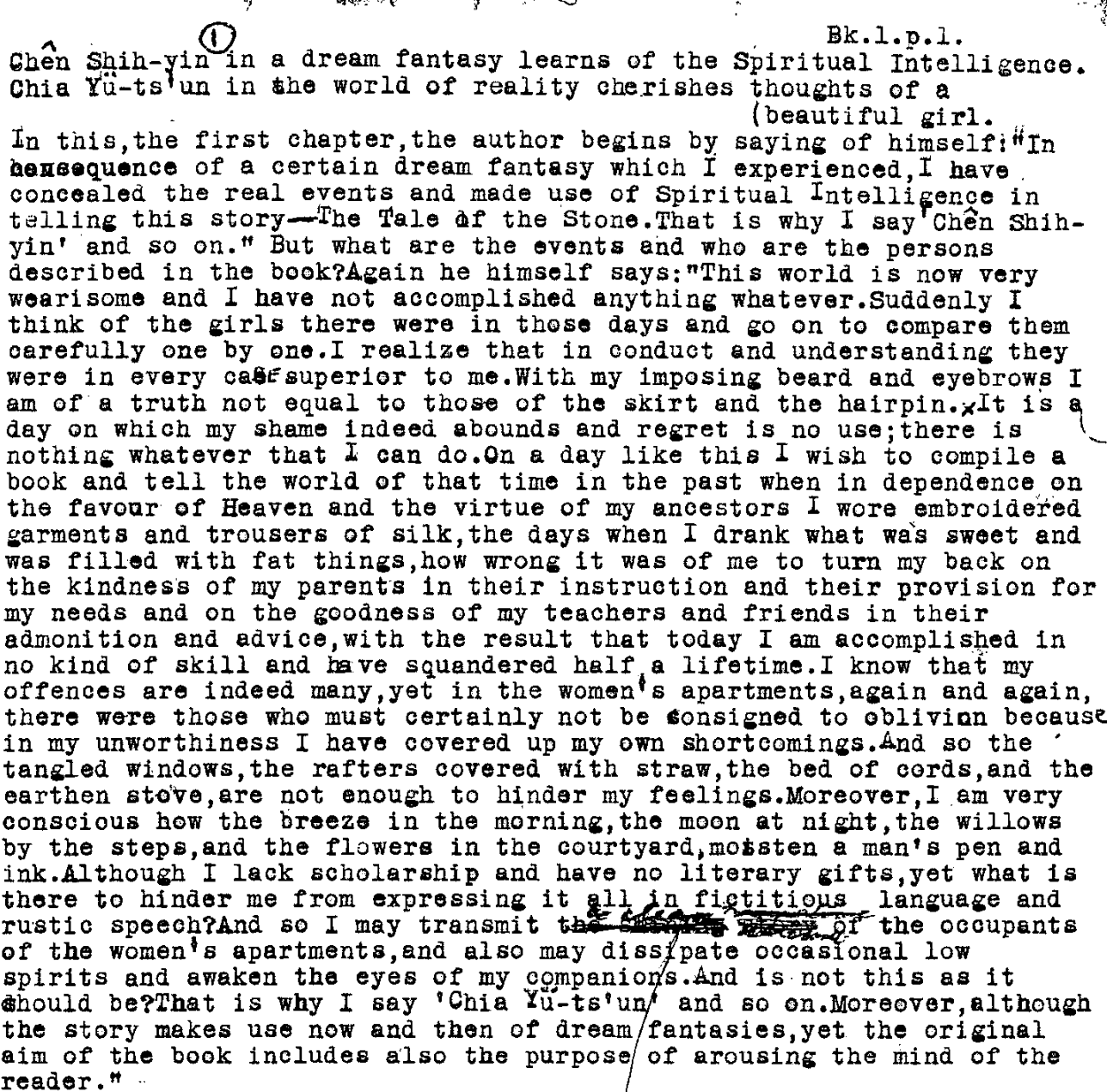

The Dream of the Red Chamber or Hung Lou Meng by Henry Bencraft Joly

Joly was the earliest scholar to attempt a complete translation of 紅樓夢 in English. He got only about 56 chapters into it.

His translation is awful. The translation is word-for-word at certain points, and there are common idioms that Joly doesn’t recognize.

Joly’s English is also simply awful. Take this example from the first page:

Wearied with the drudgery experienced of late in the world, the author speaking for himself, goes on to explain, with the lack of success which attended every single concern, I suddenly bethought myself of the womankind of past ages.

The whole thing is a bunch of gibberish. Avoid this at all costs.

Dream of the Red Chamber by Chi-Chen Wang

This isn’t a “translation” so much as a paraphrasing of the book. This particular abridgement was published in 1958.

The Dream of the Red Chamber by Franz Kuhn

This is an English translation of Franz Kuhn’s German abridgement of the book. Kuhn ripped out huge chunks of the book, leaving us with a little bit of story and little more. This version is easy to spot because it begins with “Our story begins in Suchow, the strong city situated in the southeast edge of the great plain of China.” The English version was published in 1958; the German version was published way back in 1932.

Red Chamber Dream by B.S. Bonsall

This was available on the Hong Kong University website for years. But, like other good things, it disappeared one day.

Thankfully, it is still accessible through The Internet Archive.

You can read the translation and decide for yourself. Hawkes and Yang are far better, in my opinion.

Why We Need A New English Translation

紅樓夢 is difficult to read if you’re a native speaker of Chinese. It can feel almost impossible if you’re a foreigner.

However, we’ve got access to many more resources today than we ever had before. There are databases filled with old Chinese texts. Study after study has been made on religion and mythology in ancient China. We know a lot more about the world around this novel than we ever knew.

We also have the ability to publish things a bit at a time, and to comment extensively on our translations. No longer are our translations limited to the dead words on printed paper. They can be living translations, translations that the reader can engage with, translations that allow for comments and debate and discussion.

We need a new translation to help this book live. And we desperately need somebody to kindle interest in this book.

Look — this isn’t an abstract book dealing with problems that left this world long ago. Dream of the Red Chamber is a poignant and insightful critique of society itself. It’s a book that everybody should read at some point in time, and it’s a book that we should discuss far more often than we do.

Bad translations end up gathering dust on the bookshelf, even if the entire academic community showers it with praise. So let’s make a new translation — one that people will actually want to read.

Please consider becoming a paying subscriber to this blog if you haven’t already. Your help makes this project a reality — and will keep this book alive and relevant for generations to come.