The Heart Of The Mansion

No, Lin Daiyu didn’t discover some sort of sexual secret or financial secret or anything like that. Instead, Cao Xueqin has Lin Daiyu take a detour that takes her right to the very center of the Rong Mansion. She spots a peculiar painting there that says a lot about the true ambitions of the Jia family. This might be a short passage, but there’s a lot going on here.

My Translation

Daiyu soon arrived at the Rong Mansion and exited the carriage. There was a wide paved path in front of her leading straight to the main gate. The older maids there guided her through a hallway to the east and past the southern main hall, where they reached a grand courtyard inside the ceremonial gate. Five imposing main halls stood in front of her, flanked by small rooms on both sides. There were roof ornaments made of deer antlers on the gabled passageways, with interconnected paths extending in all directions. This was quite a majestic site, and was unlike anything she had seen elsewhere.

Daiyu knew at once that this must be the heart of the mansion. As she entered the hall, she looked up and saw an enormous plaque of red gold against a blue background. The plaque was adorned with nine dragons. Upon the plaque were three bold and large characters proclaiming that this was the “Hall of Glorious Happiness.”

Beneath it, in smaller characters, was inscribed: “Bestowed upon Jia Yuan, Duke of Rongguo, on” followed by a date. The “Imperial Brush of Ten Thousand Affairs” seal was impressed beside it. There was a large purple sandwood desk that was carved with dragon figures. On top of it was an ancient bronze tripod, which was about three feet tall and was colored blue and green. Above this hung a large ink painting of a dragon awaiting the start of court at dawn.

There was a ritual vessel on one side inlaid with gold decorations, and a glass basin on the other side. Along the floor were two rows of armchairs with circular backs, sixteen in all. On the sides of the hall were a pair of plaques made of ebony wood inscribed with golden characters. They proclaimed:

The pearls of wisdom upon these seats shine like the sun and moon;

Silken robes before this hall outshine the mist and dawn.

Underneath, a small note identified the calligrapher: “Respectfully inscribed by your younger brother in worldly virtue, Mu Shi, Hereditary Prince of Dong’an Commandery.”

Translation Critique

Hawkes

David Hawkes translates 嬤嬤 as “the old nurses,” which bothers me the more I think about it. There’s no question that these are elderly women, but it’s clear from the context that these are older maids. We’ll see as we continue that Hawkes is stuck on this concept of “wet nurses” serving in the palace, something that doesn’t really seem to fit in with the context.

Hawkes correctly identifies 鹿頂 as a specific architectural design, calling it “stag’s head roofing.” This is actually really impressive considering how specialized that kind of architectural design is.

Hawkes then adds in a little bit of commentary. He misses the image of the dragon awaiting court, instead translating 待漏隨朝 as “a dragon emerging from the clouds and waves,” However, he then adds in that this is “the kind [of painting] often presented to high court officials in token of their office,” which is not in the original text.

I’ve also got a problem with how Hawkes translates the couplet:

May the jewel of learning shine in this house more effulgently than the sun and moon.

May the insignia of honour glitter in these halls more brilliantly than the starry sky.

“Insignia of honour” is not a correct translation of 黼黻; it’s simply wrong. The point is not the symbol on the robes, but the robes themselves and what they represent. Similarly, “starry sky” is not a correct translation of 煙霞 (clouds and mist; a symbol of the dawn).

But the bigger problem here is that Hawkes makes the couplet feel like some sort of blessing on the house. It’s not. It’s a somewhat sly demonstration by Cao Xueqin of the imperial aspirations of the Jia family.

It’s sad to say this, but I get the feeling that Hawkes has missed the entire point of this scene.

Yang

The Yangs follow David Hawkes in translating 嬤嬤 as “nurses.” Note that the first volume of The Story of the Stone had been published by the time the Yangs published their translation. There are numerous points where it seems that the Yangs took translation inspiration from Hawkes; I think this is one of those points.

Their translation of the poem is also interesting:

Pearls on the dais outshine the sun and moon;

Insignia of honour in the hall blaze like iridescent clouds.

Here we see “insignia of honour” again, which almost certainly takes inspiration from Hawkes. The Yangs missed that the pearls are pearls of wisdom, and, like Hawkes, seem to not realize why Cao Xueqin wrote this poem in this particular part of the story.

They also claim that the writer of the poem “styled himself a fellow provincial and old family friend,” which does not exist in the original.

Chinese Text

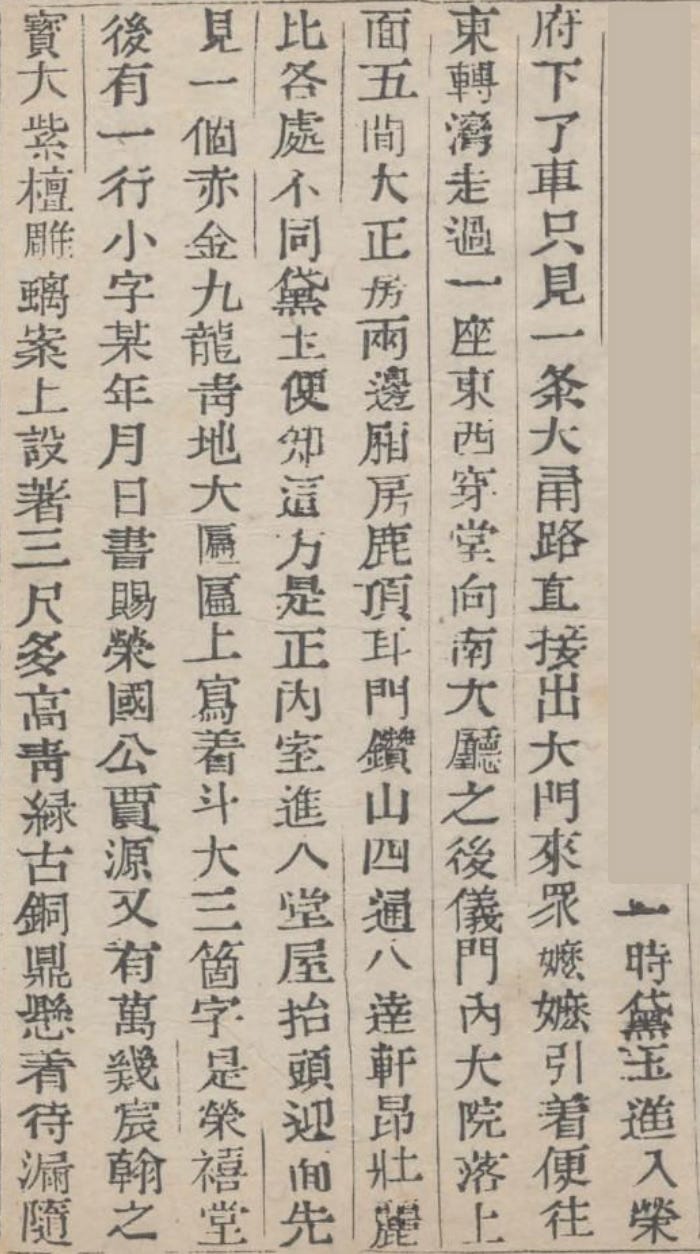

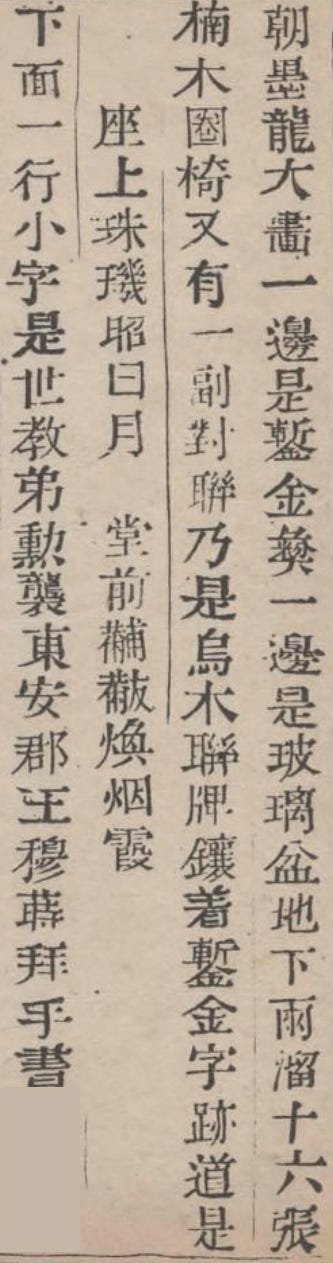

一時,黛玉進入榮府,下了車,只見一條大甬路,直接出大門來。眾嬤嬤引著,便往東轉彎,走過一座東西穿堂,向南大廳之後,至儀門內大院落。上面五間大正房,兩邊廂房,鹿頂耳門鑽山,四通八達,軒昂壯麗,比各處不同。黛玉便知這方是正內室。進入堂屋,抬頭迎面先見一個赤金九龍青地大匾,匾上寫著斗大三個字是「榮禧堂」。後有一行小字:「某年月日書賜榮國公賈源」,又有「萬機宸翰」之寶。大紫檀雕螭案上設著三尺多高青綠古銅鼎,懸著待漏隨朝墨龍大畫。一邊是鏨金彝,一邊是玻璃盆。地下兩溜十六張楠木圈椅。又有一副對聯,乃是烏木聯牌,鑲著鏨金字跡,道是:「座上珠璣昭日月,堂前黼黻煥煙霞。」下面一行小字是:「世教弟勳襲東安郡王穆蒔拜手書。」

Translation Notes

The phrasing here is a bit odd. In Chinese, Daiyu first “enters the Rong Mansion” (黛玉進入榮府) before she exits the carriage (下了車). It’s possible that “enters the Rong Mansion” might refer to entering some sort of gate while still in the vehicle.

Terms like 嬤嬤 (mómo) refer to elderly female servants. Sometimes you’ll see them translated as “wet nurse,” but that’s inaccurate given the context.

In the Chinese original, after she turns east (往東轉彎), Lin Daiyu “walks through an east-west hallway” (走過一座東西穿堂). I’ve simplified this a bit in the translation, since it seems redundant in English.

鹿頂 literally means a deer antler roof. According to Taiwan’s Ministry of Education online dictionary, this refers to the place where north-south and east-west oriented buildings meet. This helps explain the earlier mention of Daiyu going through an east-west hallway and arriving at a passage heading south: the 鹿頂 would have marked that transition. 耳門 refers to side gates or doors that connected adjacent wings or pathways. And 鑽山 (literally “piercing mountain passages”) are covered corridors that were a sort of tunnel linking courtyards together. Each of these three terms can be difficult to find online due to numerous buildings that use components of these words in their names.

四通八達 is an idiom meaning “to extend in all directions.” Here it refers to the passageways.

The phrase 比各處不同 seems to be deliberately ambiguous. It’s not clear whether Cao Xueqin is saying that the Rong Mansion was more stately and imposing than any other building on earth, or whether it simply seemed that way to Lin Daiyu. My guess is that he’s describing it from Lin Daiyu’s perspective.

And, if this is confusing to you, that seems to be the point. 鹿頂耳門鑽山 is a densely layered image, even in Chinese; in fact, my English translation is almost certainly not jarring enough to give a good sense of the feel of the Chinese original. The overall feeling here is that Lin Daiyu is completely overwhelmed by these architectural features that spread out all around her (四通八達) as far as she can see. This is a good example of Cao Xueqin’s ability to use the structure of literary Chinese to achieve a certain artistic effect.

正內室 means the main inner room of the entire mansion.

斗 means a dipper or a cup-like object, and is a pretty common word today. It also refers to a unit of dry measure for grains. 斗大 is interesting: a 斗 container was used to measure grain, and was probably about 10 to 12 inches wide. In this case, 斗大 is a descriptive phrase meaning huge and boldly visible characters. Cao Xueqin uses a common farm tool (斗) as a contrast to imperial splendor (i.e. the 9 dragons). And, as we’ll see eventually, the Jia family’s luxury and wealth is actually rooted in land rentals and grain taxes: in other words, the 斗 is literally the heart of the mansion.

榮禧堂 is an interesting name. 榮 (róng) means glory or prosperity, and is the same character used for the word Rong Mansion (榮府). 禧 (xǐ) means joy, happiness, or good luck, and 堂 simply means hall. The hall itself represents worldly success, and the presence of the nine dragon plaque is a clear hint at imperial connections and pretensions.

In 某年月日, 某 is a placeholder for an unspecified date. Remember that Dream of the Red Chamber doesn’t take place in any specific year, dynasty, date, or time. It’s difficult to translate, of course; I’ve done the best I could. It’s also interesting to note that the exact day, month, and year has been faded and obscured by time – a reference to the transient, fleeting nature of this kind of glory.

萬機, also written as 萬幾, refers to the numerous government affairs handled by the head of state. 宸翰 refers to royal writing, and means that this was the Emperor’s personal calligraphy – the highest possible mark of honor.

紫檀 is usually translated as sandalwood. It’s a kind of wood that was historically valued in China and used in opulent and extravagant furniture.

螭 was a kind of hornless legendary dragon. Using a 螭 as a motif indicates that the Jia family claimed authority, but did not challenge imperial rule by using a horned dragon figure (i.e. 龍).

待漏 is interesting. 漏 (lòu) is an ancient word for a water clock, which was used to mark the time at night (since sundials were obviously useless after the sun went down). These were time keeping devices in palaces that would drip water at measured intervals to mark the five night watch periods (更). Ministers would wait outside palace gates for the water clock to signal the fifth watch (更) as part of their bureaucratic discipline. There are a lot of layers to this imagery:

The dragon waiting to attend court is a symbol of the prior power of the Jia family, referring to a time when they held real power at court.

Nobody in the Jia family goes to court at this time – a symbol of the pretense of the Jia family at this time.

The water clock itself symbolizes how time is running out for the Jia family.

And, as we’ll eventually see, the dragon (i.e. the Jia family) waits forever for a court session that never comes.

彝 (yí) is a kind of ancient ritual vessel.

玻璃盆 is a glass basin. I’m not sure if this was “peking glass” or an imported glass basin. Either way, it’s a sign of opulence.

溜 here is pronounced liù and is a classifier word for objects arranged in lines or rows.

楠木 refers to “nanmu wood,” which was frequently used for architecture in China.

對聯 technically means “antithetical couplet,” which is kind of a mouthful. It usually refers to a two line poem written vertically down each side of a doorway. It’s common to see this during the Chinese New Year.

烏木 is ebony wood, or a type of dark wood.

聯牌 is the physical medium that displays the “antithetical couplet” (對聯).

珠璣 literally means round pearls, or jewels in general. Here they are used figuratively to mean wise words.

昭 means to bring light to, though it makes no sense for the “pearls of wisdom” to enlighten the sun and moon. It almost certainly means to shine like the sun and moon in this context.

黼黻 are silk robes worn by court officials. They contained an insignia that was a combination of an image of an axe and the character 亞.

煥 means to shine on.

Is this part of chapter 3?