The Translation Paradox

When you translate a text, should you explain everything to your reader?

Do you have a responsibility as a translator to only give your reader a certian amount of information?

And how much is enough? How do you know how far to go?

Is it enough that your reader has as much information as the average native speaking reader of the book would have? Or should you deliberately provide more information to give your reader an advantage? Or, in some cases, is it even possible (or worth your time) to discover how much information the average native speaking reader of your text would have?

This is the sort of question that comes up when you translate a book like Dream of the Red Chamber into English. And, interestingly enough, the book has incredibly strong cultural connections - the sort of cultural connections that only major literary classics enjoy.

The first comparable work that comes to mind is Faust, erster Teil by Goethe.

It’s not hard to find translations and commentaries of that work. However, it’s still difficult to understand as a foreigner because you simply did not grow up in an environment in which the most famous quotes were extremely well known.

So, when you come across something like this:

Grau, teurer Freund, ist alle Theorie,

Und grün des Lebens goldner Baum.

You might want to naturally translate it like this:

Grey, good friend, is all theory,

And green is the golden tree of life.

And the translation is fine — but it doesn’t have that feeling to it. You can read the words, you can analyze the words — but you can’t really feel their impact without being completely immersed in the culture.

Dream of the Red Chamber is indeed that kind of work. Take this poem for example:

可嘆停機德

堪憐詠絮才

玉帶林中掛

金簪雪裡埋

Alas for her domestic virtue,

How unfortunate her poetic wit!

A jade belt hangs in the woods,

A golden hairpin is buried beneath the snow.

Now, it’s not hard to analyze this poem. But it is hard to get a good feeling for the poem. We can talk on and on about the obvious textual tricks here (玉帶林 is basically 林黛玉 backwards, an obvious reference to Lin Daiyu; 金簪雪 clearly hints at 薛寶釵 when you read it backwards, an obvious reference to Xue Baochai).

But the thing is that this poem has a deeper meaning outside the context of the book itself, which is precisely what we see in Goethe. The precious belt of jade hangs alone in the woods, abandoned by its world. And the gorgeous golden hairpin lies buried deep within the snow, hidden from the hustle and bustle of the outside world.

That’s the problem with translating this book. There’s so much depth to it that the translator can easily feel overwhelmed.

And so, in yesterday’s translation post, I made a big deal of talking about the word 通靈 in the title of chapter 8 and how to interpret it.

David Hawkes simply calls it “the Magic Jade” and moves on.

However, 通靈 doesn’t really mean that. It’s kind of an odd word, something similar to spiritual understanding or even spiritual enlightenment.

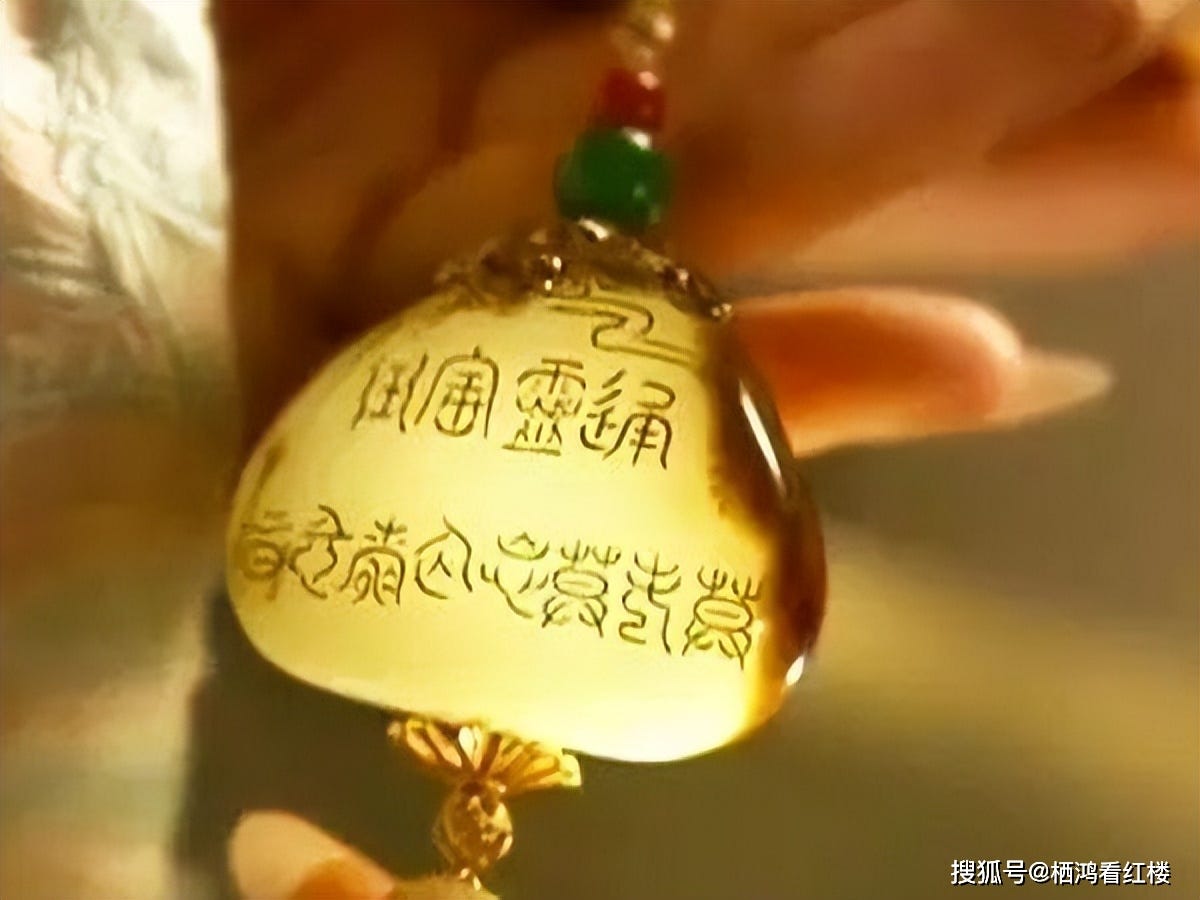

You see - when Jia Baoyu’s piece of jade is called 通靈寶玉, it’s not just a throwaway name. This isn’t just something that some geeky author thought up one day after having a little bit too much to drink.

The jade symbolizes the connection that Jia Baoyu has with his celestial origins. It’s apparently supposed to be a reminder to him of the purpose of his existence.

It’s not some sort of magic revelatory orb by which he can access the mind and will of the divine. It seems to be chiefly symbolic. And, as we saw in chapter 3, it seems that those around Jia Baoyu take it much more seriously than he does.

The cool thing about websites like The Chinese Text Project is that you can look up words like 通靈 and get an idea for what it meant at different points in Chinese history.

While performing that search, I came across a fascinating poem in the 漢書, or the official history of the Han dynasty. This comes from an extremely challenging poem that draws on even older poetic traditions as it connects the Han Dynasty with the mystic past:

素文信而底麟兮

漢賓祚于異代

精通靈而感物兮

神動氣而入微

When the plain unicorn appeared, it confirmed the virtue of the plain text,

And the Han now holds the blessing, a legacy from a different age.

When essence connects with the divine, all things are stirred;

When spirit moves the ether, it enters the subtle realms.

Here, 精, or the essence, is connected (通) with the divine, or 靈 (i.e. something spiritual).

And that’s precisely what happens to Jia Baoyu.

You see - Baoyu doesn’t own the jade. Baoyu is the jade. And the material essence (精) of his mortal existence is connected (通) with the divine (靈) through that piece of jade - the 通靈寶玉.

Now, the big question for any translator is whether the average reader of this book would think that deeply. Maybe they would, or maybe they wouldn’t. Maybe they had a knowledge of the classics that would put our Chinese Text Project to shame. Or maybe we’re going a bit too far in telling the reader all of this.

Personally, I prefer to err on the side of giving too much information instead of giving too little.