Trafficking of Women in the Qing Dynasty

We’ve just finished a pretty harrowing interlude about the fate of Zhen Yinglian, the little girl we met in the first chapter of Dream of the Red Chamber.

It turns out that this was actually a relatively common and pervasive practice in China at the time.

There are a few great books out there on the subject. Though it deals with a time period about a hundred years after Dream of the Red Chamber, the excellent Sold People: Traffickers and Family Life in North China by University of Chicago Professor Johanna S. Ransmeier is an excellent treatment of the subject.

Per Professor Ransmeier, the practice was much more complex than even Cao Xueqin described. Not only were there numerous wealthy households that kept 婢女 (bìnǚ, or slave girls), as Cao Xueqin clearly describes, but there was also a frightening and difficult to read trend of selling child brides.

In fact, it was often hard to tell children apart from the servants, as this photo clearly demonstrates:

We might think of the various servant girls in Dream of the Red Chamber in a romanticized and artistic manner. The stark reality, however, is that many servants in wealthy Chinese households looked like these children.

Interestingly, Professor Ransmeier provides a glossary of terms in the appendix, none of which match the terms we’ve seen so far. 柺子, which Cao Xueqin uses for “kidnapper” or “trafficker,” for example, is nowhere to be found. Instead, it seems that the Beijing region used terms more like 渣子行 (or perhaps 渣滓行?) for “the trafficking business.”

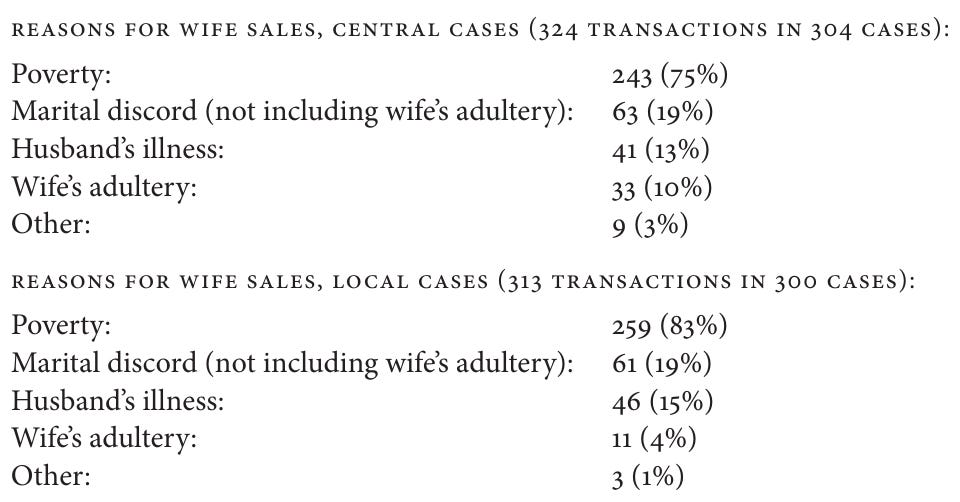

There’s another great book on a similar subject by Stanford Professor Matthew H. Sommer called Polyandry and Wife-Selling in Qing Dynasty China. Though Professor Sommer chiefly investigates court cases from specific counties in modern Sichuan Province, it seems that the cases he found were pretty common throughout the entire Qing Dynasty. It might seem hard to believe today, but it was not all that rare for husbands to sell their own wives for a variety of reasons:

Of course, the worst part of all this is that human trafficking continues to be a problem to this day — and not one merely confined to the countryside.

Dream of the Red Chamber is fascinating to those familiar with human trafficking because of the stark and realistic way in which the practice is described. Zhen Yinglian is kidnapped mostly out of convenience. It’s possible that the servant Huo Qi worked with the trafficker ahead of time; we simply don’t enough to tell.

Zhen Yinglian almost certainly wanted to obfuscate her own sad history, both in an attempt to save face and in hopes of slipping through into a better future. And, of course, the concept of buying and selling one’s own family members was certainly not uncommon:

All of this, of course, makes Cao Xueqin’s work even more bold and challenging. Cao Xueqin not only describes the practice of trafficking, but he also gives a voice to the victims in a way that his contemporaries simply didn’t.