What's In A Name?

Dream of the Red Chamber is almost certainly the most authentically Chinese novel imaginable.

There’s no question that the original was drafted in Chinese, and that it was drafted by a gifted scholar who used subtle means to get his message across. In fact, the unmistakable and undeniable Chinese nature of the work is one of the reasons why it’s so hard to translate into foreign languages. It’s really hard to bridge the gap.

One way Cao Xueqin turned what could have been an ordinary love story into an extraordinarily subversive tale was through the names he used for his characters.

We’ve already seen some of these symbolic names — though I should recap, since it’s not always easy to remember them.

甄士隱 (Zhen Shiyin) is a homophone with the phrase 真事隱, or “hiding true things.” And, true to his name, Zhen Shiyin suppresses his true rage and frustration at losing his beloved daughter, Yinglian, as well as his house, his land, and all his wealth. In the face of harsh criticism by the Taoist priest, Zhen Shiyin offers a moment of defiance (“甚荒唐,到頭來,都是為他人作嫁衣裳,” or “it’s all absurd, and, in the end, I’m just making a wedding dress for another girl” — an obvious reference to a well-known Tang poem and a fascinating example of a character crossing gender lines), and then hides his displeasure, abandons everything in his life, and goes along with the priest.

賈雨村 (Jia Yucun) is a homophone with the phrase 假語村[言], “false words and country [phrases].” One key thing to remember is that the surname Jia (賈), which comes up over and over again in this novel, stands for the word 假 (false). This also reminds us that one of Cao Xueqin’s principal goals with this book is to remind his readers of the illusory nature of things in life, which he calls 幻.

封肅 (Feng Su) is the name of Zhen Shiyin’s father-in-law; his name is a homophone with the word 風俗, or customary social practices. Feng Su, of course, doesn’t have any morally sound social customs. Instead, he robs Zhen Shiyin of what little money he has, offers him a patch of poor land and a dilapidated house in return, and then criticizes Zhen Shiyin at every possible opportunity.

甄英蓮 (Zhen Yinglian) is the name of Zhen Shiyin’s daughter. 英 means “hero,” and 蓮 is a lotus — both a symbol of purity rising from the mud and a symbol of transience, since the flower withers quickly. Her name reminds the reader of the old Song dynasty short essay “Ode to the Lotus” (愛蓮說) by Zhou Dunyi (周敦頤). There’s a famous passage that says 予獨愛蓮之出淤泥而不染,濯清漣而不妖;中通外直,不蔓不枝;香遠益清,亭亭淨植,可遠觀而不可褻玩焉, which means “But I alone love the lotus — rising unsullied from the mud, bathed in clear ripples yet free of garish charm; hollow within, straight without, spreading no creeping vines or tangled branches; its fragrance purer with distance, standing tall and pristine, to be revered from afar but never profaned with trifling touch.” As we’ll see, Yinglian winds up a maid in the Jia family, which means she travels from truth (真) to falsehood (假). Her name will change twice — and both name changes are symbolic.

林如海 (Lin Ruhai) is Lin Daiyu’s father. His given name is 林海 (Lin Hai), which isn’t much different in meaning from Lin Ruhai. His name has the odd combination of stability (林 means forest) and unpredictability (海 means the ocean; 如海 means “like the ocean”). Though his family line is rooted in scholarship and prominence, he is prone to whatever fate awaits him, as if he were on the ocean.

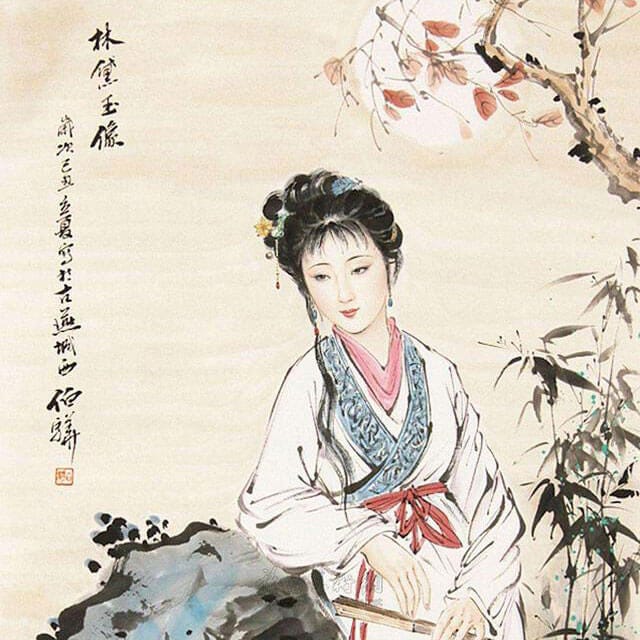

And then we get to Lin Daiyu (林黛玉), whose name is even more interesting.