What’s In A Name?

Do you know why it feels like we’re going at a snail’s pace? It’s simple. It’s because the passages we’re reading are filled to the brim with interesting stuff. And it’s honestly hard to figure out just where to begin.

Yesterday we met a man named Qin Bangye (秦邦業). It seems that his name in the handwritten manuscripts was originally given as Qin Ye (秦業). This is reflected pretty clearly in the Gladys Yang translation (A Dream of Red Mansions).

Of course, the Yangs don’t always cite their sources or tell us what is going on, which is particularly frustrated for those of us struggling to get through the material. Fortunately, though, there are online sources that make it a little bit easier to figure things out.

This essay (in Chinese) on the Epoch Times website is extremely helpful. And I’ll do my best here to stick to the main ideas of the essay and explain to you what I think is going on.

The name Qin Ye (秦業) seems to be a homophonic pun. According to the Epoch Times article, it seems to stand in for the phrase 情孽, which could mean something like “sinful passion,” though it probably means more than just that. And this isn’t speculation, either. According to the article, this connection was specifically made by the famous “Zhiyanzhai” (脂硯齋) commentator in at least one handwritten manuscript.

Like you, I’m still studying. I’m trying to learn as much as I can about this book and what it really means while I’m reading it, and it’s sort of like learning how to chew bubblegum and walk at the same time. 情 is usually translated as something like “passion” or “romance” or even “emotion,” but the truth is that it had a lot of literary significance, especially in the later years of the Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty. In fact, it’s so significant that I probably should devote yet another article just to dive into it.

The word 孽, on the other hand, means “sin” or “karmic debt.” And the connection that Zhiyanzhai makes is that this passion (or 情) arises from that sin (孽).

So what was the passion? And why does this matter?

Well, we know already that Qin Keqing is rumored to be involved in an adulterous affair with her father-in-law. That’s what the crazy servant was screaming about at the end of chapter 7:

那裡承望到如今生下這些畜生來!每日偷雞戲狗,爬灰的爬灰,養小叔子的養小叔子,我什麼不知道?

Who would have known they’d end up breeding a pack of animals like this? Day in and day out, it’s all about chasing hens and hounds. The father defiles his own daughter-in-law, and the woman throws herself at her younger brother-in-law. Is there anything I don’t know?

Jiao Da, the old and surly servant who was screaming out all this stuff, was directly implicating both Qin Keqing and Wang Xifeng, the two women who were in front of him. And, just like the crazy old peasant woman in the film version of The Princess Bride, it seems that this character was created to give the reader an important clue.

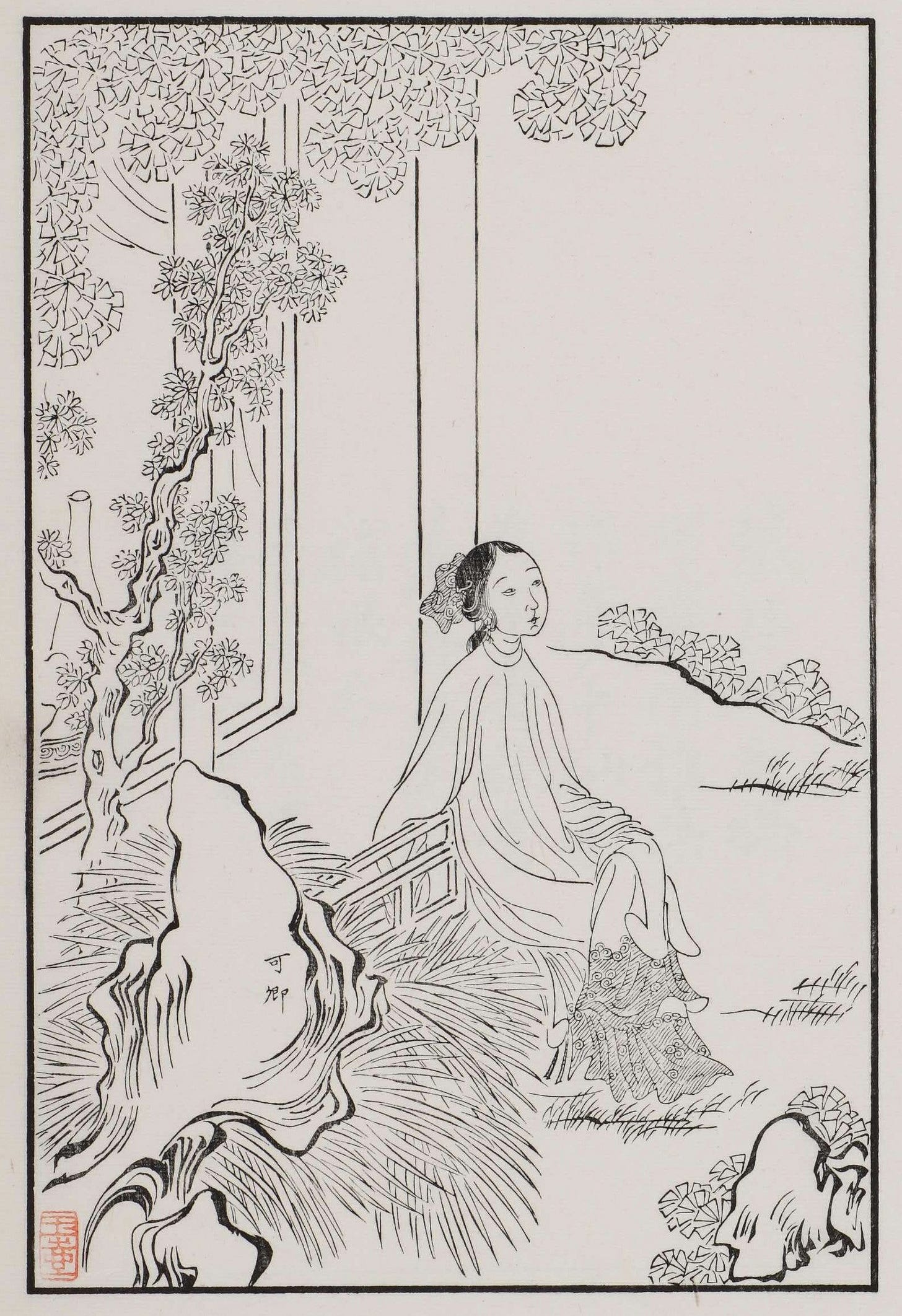

The implication is that Qin Keqing has a sexual relationship with her father-in-law Jia Zhen. In fact, as the article clearly states, the original manuscript contained a section named 秦可卿淫喪天香樓, or “Qin Keqing dies licentiously in the Celestial Fragrance Pavilion,” which was later deleted and changed. The implication, of course, is that she took her own life in the original manuscript in direct connection with the adulterous and incestuous relationship she had with her father-in-law.

Did you ever think this book was boring?

Anyway - this is all a bunch of family gossip, sure. But the cool thing about this is that it explains a passage that David Hawkes didn’t understand.

The final poem in Chapter 5 reads like this:

好事終

畫樑春盡落香塵。擅風情,秉月貌,便是敗家的根本。箕裘頹墮皆從敬,家事消亡首罪寧,宿孽總因情!

Good Things Must End

The fragrant dust falls from the painted beam at the end of the spring.

Indulging in romance and being breathtakingly beautiful

Is the reason for the family’s breakdown.

The neglect and collapse of the family’s legacy started with Jing,

But the chief culprit in the downfall was Ning,

And the root cause was always emotion.

This is a direct reference to the end of Qin Keqing’s life. And the fact that it remains in this book despite the changes to other parts of the manuscript is actually really interesting.

I know I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating. The reference to the painted beam (畫樑) is a direct literary reference to suicide. “Romance” or “emotion” or whatever we want to name it actually the same word in Chinese: 情. And we see three key facts:

The collapse of the Jia family legacy started with “Jing,” or Jia Jing (賈敬), who is Jia Rong’s grandfather and thus Qin Keqing’s grandfather-in-law;

The direct instigator of the collapse was “Ning,” or 寧, which refers to the 寧國府, or the Ningguo Mansion; and

The sin (孽) was always caused by Qing (情).

There’s that odd coupling of 情 and 孽 again.

As I’ve mentioned before, David Hawkes comments extensively in his appendix about Lin Daiyu and Xue Baochai somehow being two halves of the perfect woman, which he interprets as being represented in the name Jianmei (兼美). That name literally means “both beauties” or “the combined beauties.” And my understanding is that Zhiyanzhai apparently mentions something similar in a commentary entry somewhere, though I’ll have to rely on the comment section to tell me precisely.

The problem with this interpretation, however, is that Lin Daiyu and Xue Baochai are not perfect foils of each other. And, above all, Qin Keqing is not the embodiment of the bits of perfection that both of Jia Baoyu’s main love interests have.

Instead, that Epoch Times article notes that Grandmother Jia thought highly of Qin Keqing. As a result, Grandmother Jia was more than happy to let Jia Baoyu sleep in Qin Keqing’s room, not knowing just how erotic it was. But the truth is that Qin Keqing’s outer image was a sharp contrast to the sort of person she was on the inside.

If you take a step back and look at the whole book, you’ll realize that Jia Baoyu’s sexual awakening took place in Qin Keqing’s bedroom. And, since that sexual awakening sparks a chain of events that really gets the story moving, you could argue that the root of all of Jia Baoyu’s later unhappiness was that slumber in her bedroom. This might be the reason why Qin Keqing is the person the Goddess gives to Jia Baoyu for his first dreamlike sexual experience.

Anyway, there’s more to the article than just this, and I’m summarizing a bunch for the sake of time. But Qin Keqing’s actual role in this book is fascinating - and it’s a lot more complex than what David Hawkes surmised.