Why You Should Read Dream Of The Red Chamber

The thing that amazes me the most about Dream of the Red Chamber is the fact that it remains relevant even today.

We have a tendency to think that the problems that we face in modern society are somehow different from the problems we’ve faced in the past. There’s a general feeling that learning history is only important for those who care about trivial information, and that classical literature is really only important to read if you’re planning on becoming an expert in the classics.

The funny thing, of course, is that this isn’t a particularly modern attitude. You can find similar feelings in all countries throughout the course of human history, actually. Most people tend to care only about the problems that they face today, and aren’t really interested in looking elsewhere for unusual or creative solutions - even if certain books might hold special insights into their problems.

I know I’m being sort of vague, so let’s get straight to the point.

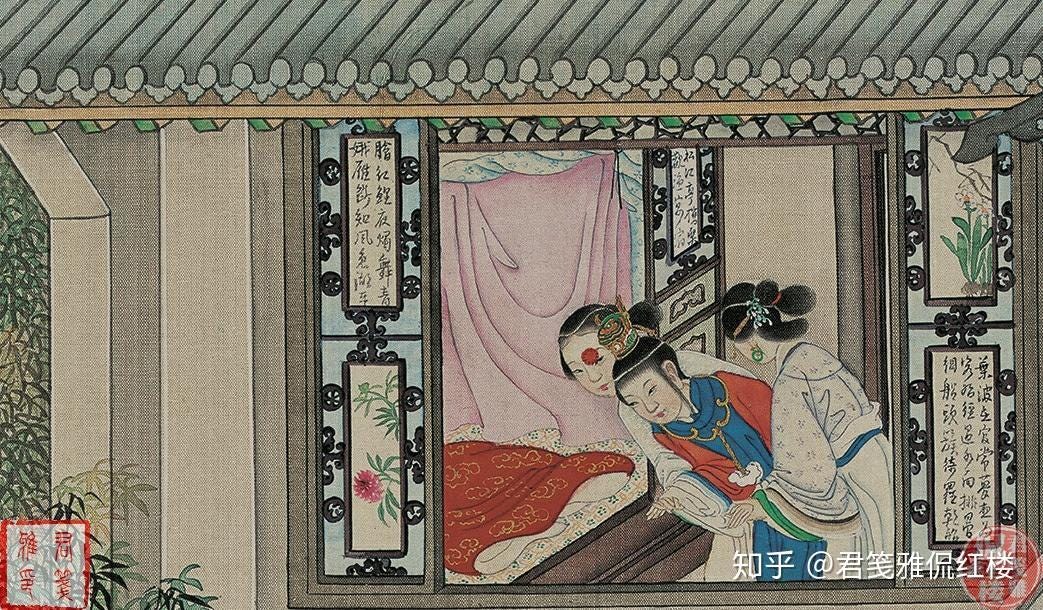

As Jia Baoyu and Wang Xifeng visited Qin Keqing on her sick bed in yesterday’s post, they both reacted in different ways to seeing her sickly state.

Qin Keqing is strangely cognizant of her coming demise, and says so as Wang Xifeng holds her hands:

我自想著,未必熬得過年去!

The way I feel now, I doubt I’ll last the rest of the year!

Jia Baoyu found himself lost in the beauty of the painting and poetry on her wall. It took him back to chapter 5, back when Jia Baoyu fell asleep in Qin Keqing’s bedroom and had a vision of the things that were bound to happen to all of the women he knew and loved.

As you might remember, Jia Baoyu had a sexual encounter at the end of that dream with a dream girl who shared Qin Keqing’s name:

Now, there’s no evidence that Jia Baoyu actually has some sort of physical relationship with Qin Keqing. Instead, the scholarship on Dream of the Red Chamber indicates that it’s likely that Qin Keqing was originally supposed to have an affair with her father-in-law, Jia Zhen, but that this was taken out during the editing process of the book.

But you can still understand Jia Baoyu’s emotional reaction to having his thoughts interrupted by Qin Keqing’s awful prediction:

正在出神,聽得秦氏說了這些話,如萬箭攢心,那眼淚不覺流下來了。

He was lost in these thoughts when he heard what Qin Keqing had said. Her words pierced his heart like a thousand arrows. Despite his best efforts, tears began to fall from his eyes.

This is a classic example of Jia Baoyu’s natural character. From the beginning of Dream of the Red Chamber, he is closely associated with the concept of 情, a difficult word to translate that can mean “passion,” “feeling,” “emotion,” or a host of other related concepts.

It turns out that discussions around 情 were common in Chinese literary circles in the two centuries or so before Dream of the Red Chamber was first published. For example, there was the so-called “Revivalist movement” (復古, or “reviving antiquity”) of the late 15th and early 16th centuries:

The “qing” mentioned in this passage is 情 - that difficult to nail down concept of emotion.

Anyway, we don’t really need to spend a ton of time going through old literary movements and learning all the trivia. For the sake of understanding Dream of the Red Chamber, it’s enough to just know that this was a thing that was being discussed in Chinese literary circles for centuries before this book was written. And the biggest concern seems to have been that literature had lost a lot of its feeling in favor of nothing but bland formality.

Jia Baoyu, like Lin Daiyu, is the embodiment of this concept of 情. As such, Jia Baoyu is entirely unable to prevent his emotions from showing, even though he might want to stop himself.

Wang Xifeng’s reaction to Jia Baoyu’s tears is also telling:

鳳姐兒見了,心中十分難過。但恐病人見了這個樣子反添心酸,倒不是來開導他的意思了,因說:「寶玉,你忒婆婆媽媽的了。他病人不過是這樣說,那裡就到這個田地。況且年紀又不大,略病病兒就好了。」

Xifeng was extremely sad when she saw this. However, she worried that displaying such sorrow would only make Qin Keqing feel worse, and would defeat the purpose of her visit. “Don’t act like such a little girl!” she admonished Baoyu. “Of course she’ll talk like that; after all, she’s sick. But she hasn’t reached that stage yet. Besides, she’s young; an illness like this will pass away in no time.”

My first reaction when I read this passage was that Wang Xifeng was basically telling Jia Baoyu to suck it up. In other words, her response is to tell him to suppress his emotions and act like nothing is happening.

Wang Xifeng naturally knows that Qin Keqing is really in a bad state. However, she’s convinced herself that the best way to handle the problem is to pretend that the problem isn’t there. And so she ignores the obvious and offers only a few empty platitudes, hoping that this will at least calm everybody’s emotions down.

But doesn’t this sound unusually modern to you?

Jia Baoyu simply cannot control his emotions because of the kind of person he is. And yet the society around him tells him that he has to control his emotions, that he has to bottle them up and pretend that nothing is happening.

It’s the emboidment of machismo, the concept that the only way to be manly is to never show emotion or weakness no matter what happens. And the concept that men have feelings that need to be expressed is really something that we only see in modern times.

Except, of course, in Dream of the Red Chamber.

There’s a lot we can learn from this novel of the mid-18th century. Stick with me on this journey, because we’ve still got a lot to uncover.

Great point about emotional suppression vs machismo being tackled centuries ago. The Jia Baoyu/Wang Xifeng contrast really nails how emotional authenticity gets pathologized as weakness while performative stoicism gets normalized as strength. That tension between qing and social propriety feels timeless, but seeing it articulated so clearly in 18th-century lit is kinda wild. Makes alot of "modern" psychological insights look less novel than we think.