Xue Baochai Sees The Jade

Xue Baochai has a chance to take a close look at Jia Baoyu’s jade in this passage. This includes a poem that is difficult to understand, but is filled with the sort of symbolism that characterizes this novel.

My Translation

“Are you better now?” Jia Baoyu asked her as he looked closely at her.

Xue Baochai looked up and saw Baoyu entering. She quickly rose to her feet and smiled at him. “I’m much better now,” she replied. “Thank you for thinking of me.” As she said this, she invited him to sit on the edge of the couch and asked Ying’er to serve tea.

As Baochai asked him about the health of Grandmother Jia and Lady Wang, as well as how her other female cousins were, she took a close look at his appearance. She saw that he had a shiny gold crown on his head, decorated with precious gems inlaid in a golden pattern. On his forehead was a tight band embroidered with the “two dragons contending for a pearl” motif. He wore a yellow-green jacket with white lining made of fox fur, embroidered with the image of a sitting python and with tight sleeve cuffs designed for archery. There was also a five colored sash around his neck, embroidered with butterfly motifs. He had a “long life lock” amulet around his neck, as well as a name amulet.

And, of course, there was also the Precious Jade of Spiritual Understanding that was in his mouth when he was born.

“I’ve always heard about that famous jade of yours,” said Baochai with a smile. “But I’ve never had a chance to take a good look at it. I’d love to see it now,” she said as she drew nearer.

Baoyu also moved closer. He took the jade off from his neck and put it in Baochai’s hand. She held it in her palm. It was the size of a sparrow’s egg, as colorful as a rainbow cloud, as luminous and smooth as butter, and encircled by a protective vein of colorful veins.

Dear reader, you should understand that this was the illusory form taken by the useless stone that we saw below the Boundless Cliff of the Great Wilderness Mountain. A poet later wrote these lines mocking it:

Nüwa’s smelting of the stone was an absurd tale,

And now we tell an even more absurd story on top of it.

Its original true face has been lost,

And it must now exist covered in stinking flesh.

Know that the gold will lose its color when fate fails,

And lament that the jade will not shine true when bad luck arrives.

As the white bones pile up in a mountain, family lineage is forgotten,

In the end, they were nothing more than young men and beautiful women.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

As usual, David Hawkes’ insistance on making the poem rhyme takes a bit away from the meaning.

His translation of the third and fourth lines read like this:

Lost now, alack! And gone my heavenly stone –

Transformed to this vile bag of flesh and bone.

I think Hawkes had to resort to this awkward phrasing because he couldn’t figure out any other way to get things to rhyme. The line 失去本來真面目 actually refers to the stone losing its “true identity” because it came to earth in the physical form of Jia Baoyu. I guess that explains the reference to “my heavenly stone,” though it really doesn’t make much sense without at least some sort of commentary.

Yang

The insistence on rhyming also makes the Yang translation of the poem difficult to understand.

Here’s how it starts:

Fantastic, Nu Wa’s smelting of the stone,

Now comes fresh fantasy from the Great Waste;

The Stone’s true sphere and spirit lost,

It takes a new form stinking and debased.

It works if you know the original poem and have read it a few times. However, if you come to this poem as an English reader unaware of the original, it’s easy to get lost. What is the “Great Waste?” Why a “fresh fantasy?”

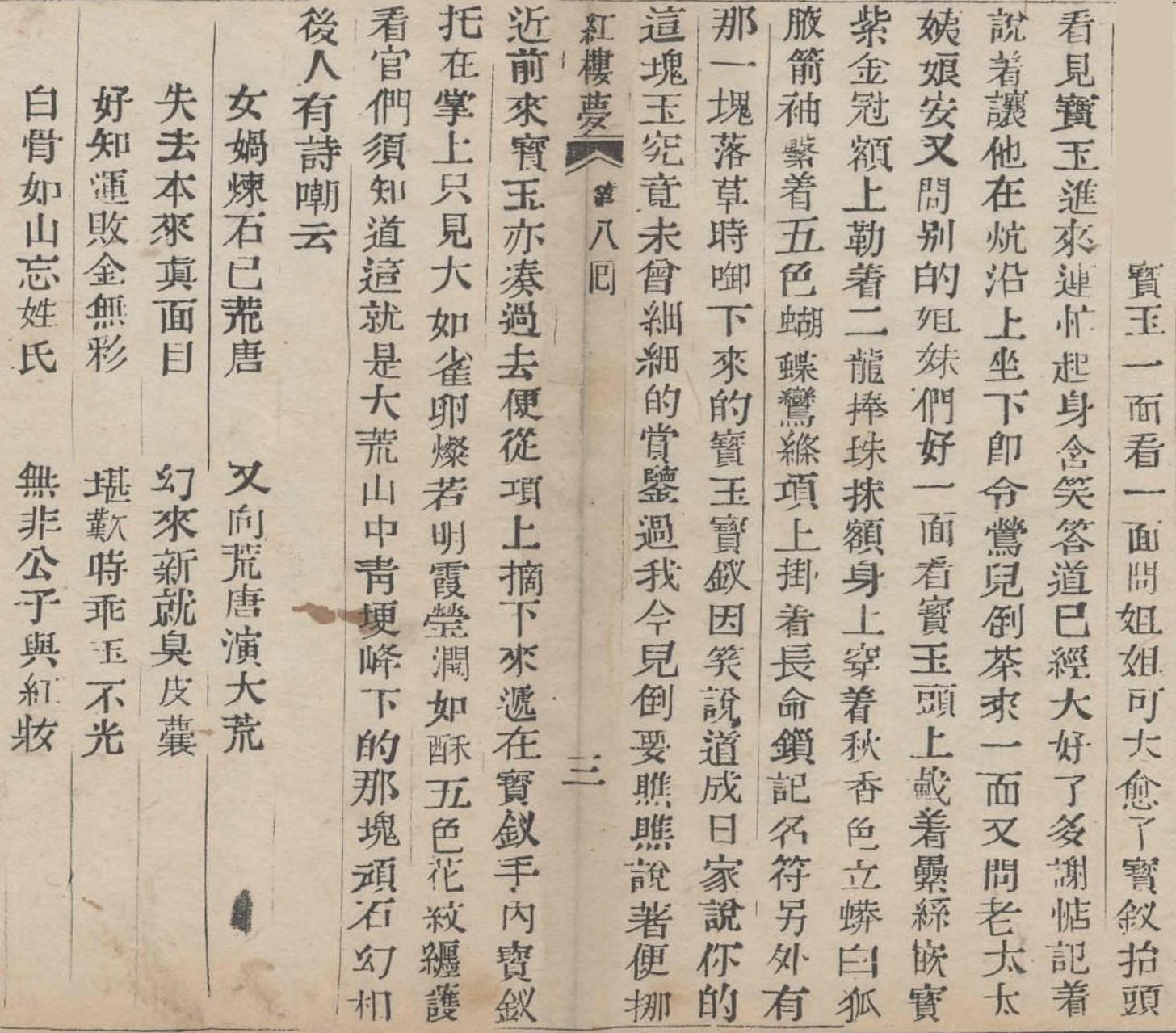

Chinese Text

寶玉一面看,一面問:「姐姐可大愈了?」寶釵抬頭看見寶玉進來,連忙起身,含笑答道:「已經大好了,多謝惦記著。」說著,讓他在炕沿上坐下,即令鶯兒倒茶來。一面又問老太太姨娘安,又問別的姐妹們好;一面看寶玉頭上戴著累絲嵌寶紫金冠,額上勒著二龍捧珠抹額,身上穿著秋香色立蟒白狐腋箭袖,繫著五色蝴蝶鸞絛,項上掛著長命鎖、記名符,另外有那一塊落草時銜下來的「寶玉」。寶釵因笑說道:「成日家說你的這塊玉,究竟未曾細細的賞鑑過,我今兒倒要瞧瞧。」說著,便挪近前來。寶玉亦湊過去,便從項上摘下來,遞在寶釵手內。寶釵托在掌上,只見大如雀卵,燦若明霞,瑩潤如酥,五色花紋纏護。

看官們,須知道這就是大荒山中青埂峰下的那塊頑石幻相。後人有詩嘲云:

女媧煉石已荒唐,又向荒唐演大荒。失去本來真面目,幻來新就臭皮囊。

好知運敗金無彩,堪嘆時乖玉不光。白骨如山忘姓氏,無非公子與紅妝!

Translation Notes

惦記 means to think about somebody with concern.

鶯兒 (Ying’er) is the name of Xue Baochai’s maid. She was introduced very briefly at the beginning of chapter 7, and we haven’t really met her yet.

紫金冠 literally means a “purple-gold” headpiece. 紫金, however, doesn’t mean a purple and gold color. Instead, 紫 (purple) is an adjective that describes a type of 金 (gold), indicating that this was a very rare and extremely expensive type of gold. The headdress was inlaid with gems (嵌寶) as part of a complex golden arrangement (累絲).

抹額 means to wrap tightly around the forehead.

立蟒 indicates a python in an upright posture, as opposed to a coiled python. The 蟒 (mǎng) was a four clawed python, indicating the highest rank of nobility below that of the Emperor; think of it as one step behind the dragon (龍) that symbolized the Emperor. This gives you an idea not only of the wealth of the Jia family, but also of the weight of the expectations placed on Jia Baoyu’s shoulders. And, as you can see, even the descriptions of Jia Baoyu’s clothing are actually descriptions of his character and personality.

The 長命鎖 (long life lock) and 記名符 (name amulet) were protective talismans given to children in order to ward off evil spirits and ensure that they would have a long life.

落草 here means to be born.

Note that the “Jade of Spiritual Understanding” is written here as 寶玉, which matches the characters in Jia Baoyu’s name exactly (賈寶玉). The full name as given in chapter 1 is 通靈寶玉, or “the precious jade of spiritual understanding.”

There’s something poetic about how Jia Baoyu and Xue Baochao move closer here. Baochai’s movement is described as 挪 (nuó; to move), while Baoyu’s movement is described as 湊 (còu; to approach or draw near). Notice that the two words sound similar, almost as if they belong together.

酥 means butter

時乖 means to have bad luck or suffer misfortune.