Zhen Yinglian Returns

The conversation between Jia Yucun and his clerk continues. I’ve broken this scene up into multiple passages because of its length; as a result, today’s post will end on a bit of a cliffhanger. This is a relatively straightforward passage in Chinese, though there are some interesting deviations from the original text in the two major English translations.

My Translation

Before Yucun could finish reading, he suddenly heard an official announcement: “Magistrate Wang is here to visit.” Yucun quickly straightened up his clothes and went out to receive the guest. He was away for about the time it takes to eat a meal – about 30 minutes – before he returned.

After he came back, Yucun questioned the clerk again. “These four families are all interconnected by marriage,” replied the clerk. “If one suffers, they all suffer; if one prospers, they all prosper. Now, the Xue family, accused of beating a man to death, is the same ‘Xue’ for whom ‘the prosperous snow falls all year round.’ Not only do they rely on the other three families, but they also have a lot of other allies and relatives, both in the capital and outside. Now, Your Honor, who do you plan to arrest?”

“If that’s the case, how should this lawsuit be resolved?” asked Yucun with a smile after he heard this. “I suppose you must know where the murder is hiding, then?”

“To be frank with you, Your Honor,” replied the attendant with a smile, “I not only know where the murderer is hiding, but I even know the trafficker involved in this case. I also am fully aware of the background of the deceased buyer.

“Let me explain this clearly to Your Honor. The victim was the son of a minor country official named Feng Yuan. He was an orphan with no siblings and lived off his meager family assets. He was around 18 or 19 years old, and was attracted to men, not to women.

“Now, this really was a case of cruel fate. He encountered the young girl by chance, and was smitten with her at first glance. He resolved to purchase her for his wife, and swore to turn away from male companionship forever and never be with another woman. And to emphasize the solemnity of this marriage, he insisted on waiting three full days before taking her into his household.

“But who could have guessed that this trafficker had already secretly sold her to the Xue family? The seller planned to run off with the money from both families. And yet before he could escape, both families caught up with him and beat him to an inch of his life.

“Neither family would accept a refund. Instead, both families demanded the girl herself. And then the young Mr. Xue gave orders to his servants, who then beat Feng Yuan to a pulp, until his body was barely recognizable. They carried Feng Yuan home, and he died within three days.

“Now this Mr. Xue had already chosen an auspicious date to go tot he capital. Having killed a man and having stolen the girl, he simply went about his business like nothing had happened. He didn’t flee because of this incident. Murder was clearly something trivial to him, and he figured that his family members and servants here could handle it for him.

“But, Your Honor, do you realize who the trafficked girl is?”

“How should I know?” asked Yucun.

“Well, it turns out that she happens to be the daughter of your great benefactor,” explained the clerk with a sardonic laugh. “She’s Zhen Yinglian, the little girl who lived next to the Bottle Gourd Temple.”

“That child?!” exclaimed Yucun in shock. “But I heard she was kidnapped at age five. How could she have only been sold just now?”

What do you think the back story could be?

Translation Critique

Hawkes

David Hawkes took some odd liberties when he translated the poem about the rich people. As a result, he can’t translate “豐年大雪” (“the prosperous snow falls all year round”) literally. The idea here is that 雪 is cognate with the family name 薛. Hawkes writes “The Xue who has been charged with the manslaughter is one of the ‘Nanking Xue so rich are they,’” which just doesn’t work.

Hawkes also handles the question of marriage rather awkwardly. The Chinese phrase is 作妾, which literally means that Feng Yuan wants to take Zhen Yinglian as a concubine (although妾 can also be translated as “female slave”). Hawkes doesn’t translate anything about any kind of wedding, but then adds a sentence at the end: “That was the idea of this waiting three days before she came to him. To make it seem more like a wedding and less like a sale.” Hawkes is correct in that Feng Yuan was actually purchasing Zhen Yinglian instead of courting her — but he’s had to add extra things into the text to get his point across.

Yang

The Yangs indicate that Feng Yuan would buy Zhen Yinglian as a concubine “and to take no other wife.” They don’t say anything about the seemingly obvious contradiction here.

Chinese Text

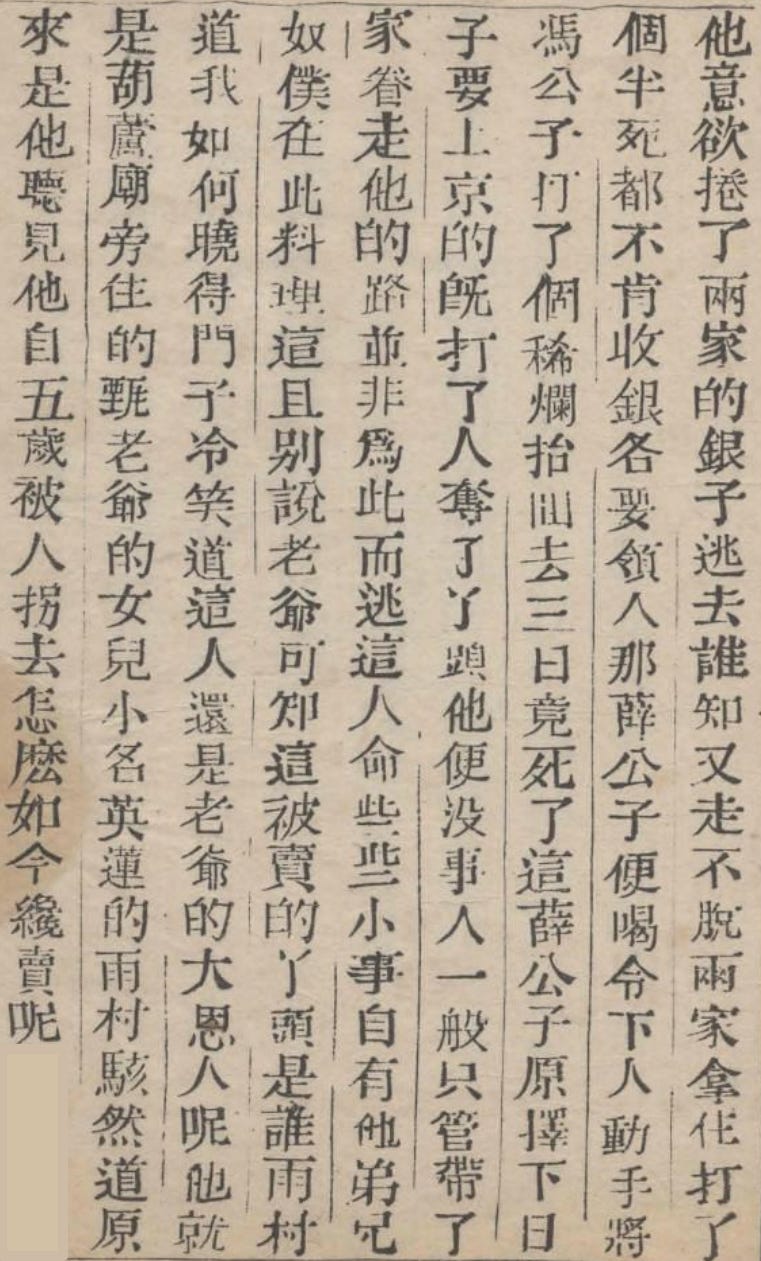

雨村尚未看完,忽聞傳點報:「王老爺來拜。」雨村忙具衣冠出去迎接,有頓飯工夫方回來。問這門子,門子道:「這四家皆連絡有親,一損俱損,一榮俱榮。今告打死人之薛,就是『豐年大雪』之『薛』。不單靠這三家,他的世交親友在都在外的本也不少。老爺如今拿誰去?」雨村聽說,便笑問門子道:「這樣說來,卻怎麼了結此案?你大約也深知這凶犯躲的方向了?」

門子笑道:「不瞞老爺說,不但這凶犯躲的方向,並這拐賣的人我也知道,死鬼買主也深知道。待我細說與老爺聽:這個被打死的乃是一個小鄉宦之子,名喚馮淵,父母俱亡,又無兄弟,守著些薄產度日。年紀十八九歲,酷愛男風,不好女色。這也是前生冤孽:可巧遇見這丫頭,他便一眼看上了,立意買來作妾,立誓不近男色,也不再娶第二個了。所以鄭重其事,必得三日後方過門。誰知這柺子又偷賣與薛家。他意欲捲了兩家的銀子逃去,誰知又走不脫,兩家拿住,打了個半死,都不肯收銀,只要領人。那薛公子便喝令下人動手,將馮公子打了個稀爛。抬回去,三日竟死了。這薛公子原已擇定日子要上京的,既打了人,奪了丫頭,他便沒事人一般,只管帶了家眷走他的路,並非為此而逃。這人命些些小事,自有他弟兄奴僕在此料理。這且別說,老爺可知這被賣的丫頭是誰?」雨村道:「我如何曉得?」門子冷笑道:「這人還是老爺的大恩人呢!他就是葫蘆廟旁住的甄老爺的女兒,小名英蓮的。」雨村駭然道:「原來是他!聽聞他自五歲被人拐去,怎麼如今才賣呢?」

Translation Notes

工夫 here means time.

The name 馮淵 (Féng Yuān) is a homophone with the phrase 逢冤 (féngyuān), which means “to encounter injustice.”

酷愛 means to have a passion for or to ardently love. 男風 is a term that refers directly to male homosexuality.

前生冤孽 literally means the retribution for sin in a past life. I’ve translated it here as “cruel fate,” in part because of the cultural difference and in part because the clerk is emphasizing his fate, not some Buddhist teaching.

買來作妾 is kind of strange. 作妾 means to act as a concubine, but this boy was only 18 or 19 and clearly was not married. It’s possible that his plan was to take her as a concubine because of the social disparity between them. Also, 妾 can also refer to a “slave woman,” though the clear romantic element here indicates that something like “wife” or “concubine” is probably correct. Note in the next sentence that he waits three days before bringing her in, which was customary for actual marriages.