Jia Baoyu Learns The Secrets

Against my better judgment, I’ve decided to take us to the end of chapter 5 today. There’s a bit of interesting philosophy here, as well as a little bit of action.

My Translation

Baoyu was frantic when he heard this.

“You are mistaken, Goddess,” he quickly replied. “My parents often scold me from being lazy and neglecting my studies. How would I dare be passionate? Besides, I’m still young. I don’t know what ‘passion’ means.”

“Wrong,” replied the Goddess. “Though there is a single principle behind ‘passion,’ that core principle manifests itself in different ways.

“Take the average libertine, or somebody obsessed with lust. All he cares about is a pretty face, dancing and singing, endless flirtation, and having sex at all hours. He’d be more than happy to be with any beautiful woman in the world for his own temporary amusement. People like this are nothing but shallow fools who debase passion with their superficiality.

“However, in your case, the gift heaven bestowed on you at birth is your deep emotional passion. People like me call this ‘the lust of the mind.’

“Now, that phrase, ‘the lust of the mind,’ can be understood by the heart but cannot be explained through speech. It can be understood through spiritual insight but not communicated through words.

“You are the only one who has been gifted with this ‘lust of the mind.’ Though you might be seen as a cherished friend in the bedrooms of women, in the wider world you will unavoidably be seen as impractical, eccentric, and strange. Hundeds of people will mock and slander you; tens of thousands will glare at you with hate and envy.

“Now, since I met with your ancestors, the Dukes of Ningguo and Rongguo, and received their deepest plea, I cannot bear for you to be cast out and rejected by the world – especially after you’ve brought such honor to my realm of maidens. And so I brought you here.

“I have clouded your senses with fine wine, I’ve awakened your spirit with immortal tea, and I’ve cautioned you with divine songs. And now I’ll give you this younger sister of mine. Her childhood name is Jianmei, and her formal name is Keqing. Tonight, in this perfect hour, you may consummate the marriage.

“I’ve done all of this to let you experience for yourself that even the splendors of the celestial woman’s bedroom are no more than this. Since this is true, what more can you expect of the mundane world?

“From this day on, you must utterly renounce these attachments, awaken from your passionate feelings, and devote your mind to the study of Confucius and Mencius, committing your life to the path of statecraft and social order.”

Having said that, she then told him in secret the facts of sexuality, pushed him into the room, closed the door behind him, and went on her way.

In a daze, as if he were in a trance, Baoyu did as the Goddess told him. And so, inevitably, the act between men and women took place. But the details are beyond our powers to tell.

By the next morning, their tender feelings had become deeply entwined. With soft words and warm caresses, he and Keqing were inextricably bound together, utterly unable to part. As the two of them held hands and went out to explore, they suddenly arrived at a certain place. All they could see were brambles and thorns covering the ground, with wolves and tigers prowling around. There was a pitch black stream blocking their path, with no bridge to cross it.

Just as they were hesitating, the Goddess suddenly came up running behind them. “Don’t go forward!” she yelled. “Turn around and go back! Hurry!”

Baoyu abruptly stopped. “What is this place?” he asked.

“This is the River of Delusion,” replied the Goddess. “It is a hundred fathoms deep, and it stretches a thousand miles in every direction. There are no boats or ferries to cross it. There is only a single wooden raft, which is piloted by the Hermit of Wood who grasps the rudder, and poled by the Servant of Ashes. They accept no payment in gold or silver, and will only ferry across those who are predestined to cross.

“You wandered here by accident. If you were to fall in, you’d deeply fail all my earnest warnings.”

Before her words ended, a sound like thunder roared from the River of Delusion. Hundreds of demonic spirits and sea ghosts seized Baoyu and dragged him down into the depths of the river.

Terrified, Baoyu broke out in a sweat that poured down like rain. “Keqing! Save me!” he cried out.

Startled by his shouts, Xiren and the other maids hurried over to hold him. “Baoyu, don’t be afraid! We’re here!” they cried.

It just so happened that Lady Qin was just outside the room, telling the young maids to carefully watch the cats and dogs who were fighting. She suddenly heard Baoyu call out her childhood name in his dream.

She was puzzled, and thought to herself, “My childhood name – how could anyone here know it? How did he find out about it, and why would he call it out in his dream?”

What was the reason for this? Find out in the next chapter.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

David Hawkes modifies things slightly in this passage. He has the Goddess distinguish between two types of “lust:” one is the man who would make love with any woman he met regardless of the circumstances, and the other consisting of Jia Baoyu’s “lust of the mind.” It’s a bit more clear than the original.

Hawkes translates the name 兼美 (Jianmei; literally “combined beauty”) as “Two-in-one.” It’s not much of a name, and it’s kind of confusing, since the translation does not make it clear that “Two-in-one” is supposed to be the name of the celestial girl.

Hawkes calls “the Hermit of Wood” (木居士) “Numb,” and “the Servant of Ashes” (灰侍者) “Dumb.” I’ve got no idea why he used these names.

Yang

The Yangs call 兼美 by her given name (“Chien-mei” in their transliteration), and include a footnote explaining that she combines the best features of Xue Baochai and Lin Daiyu.

The Yangs call 迷津 (the River of Delusion) “The Ford of Infatuation.” “Ford” or “ferry crossing” might be a better translation for 津 than “river,” though it’s hard to understand why a ford would be that deep. 迷, meanwhile, generally means something like “to bewitch” or “to infatuate” in Dream of the Red Chamber, and is kind of similar to the word 癡 in that sense. Either “infatuation” or “delusion” work in this context.

The Yangs end this chapter with a poem that is not in the original:

Strange encounters take place in a secret dream,

For he is the most passionate lover of all time.

Unfortunately, it’s not clear where these lines come from.

Chinese Text

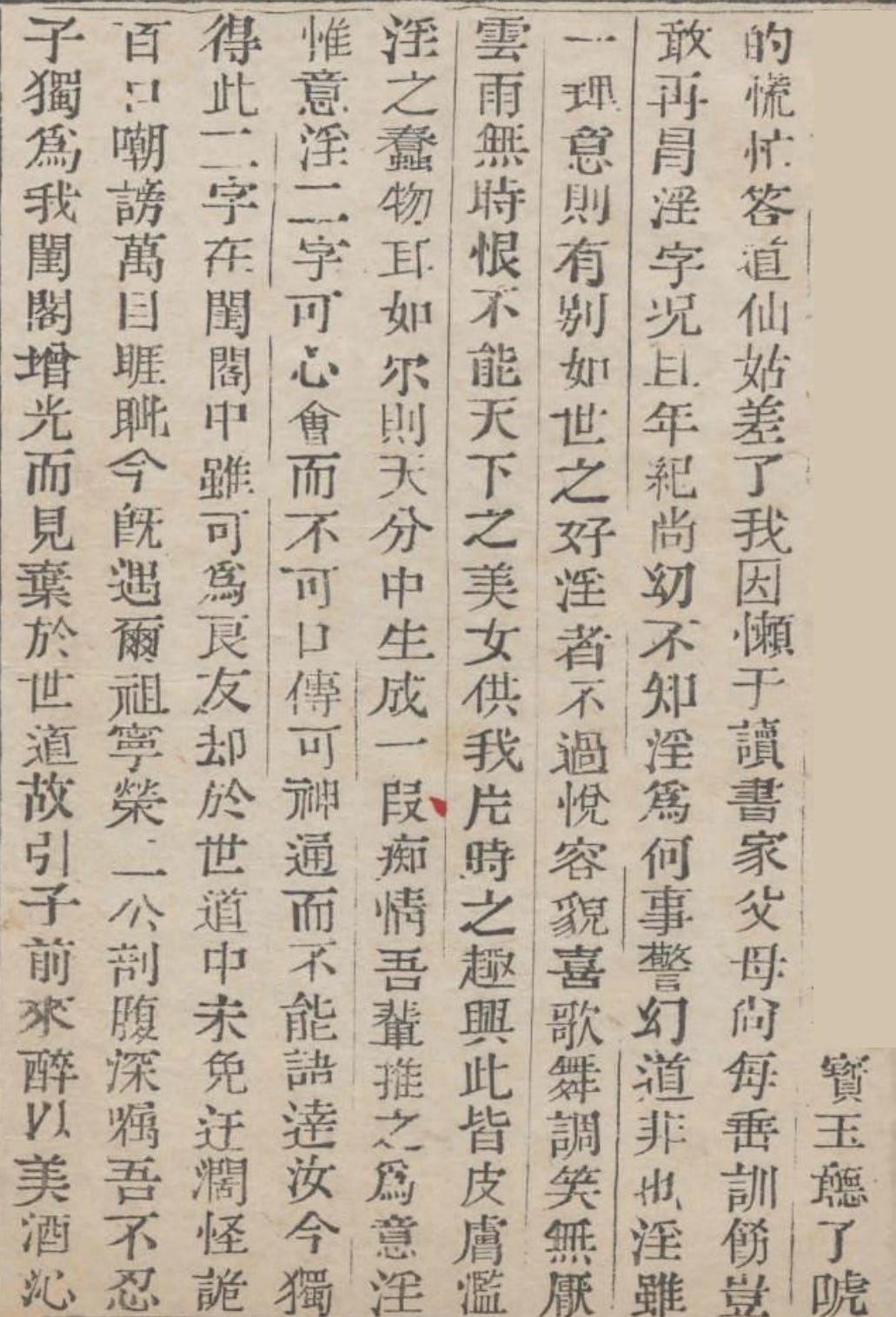

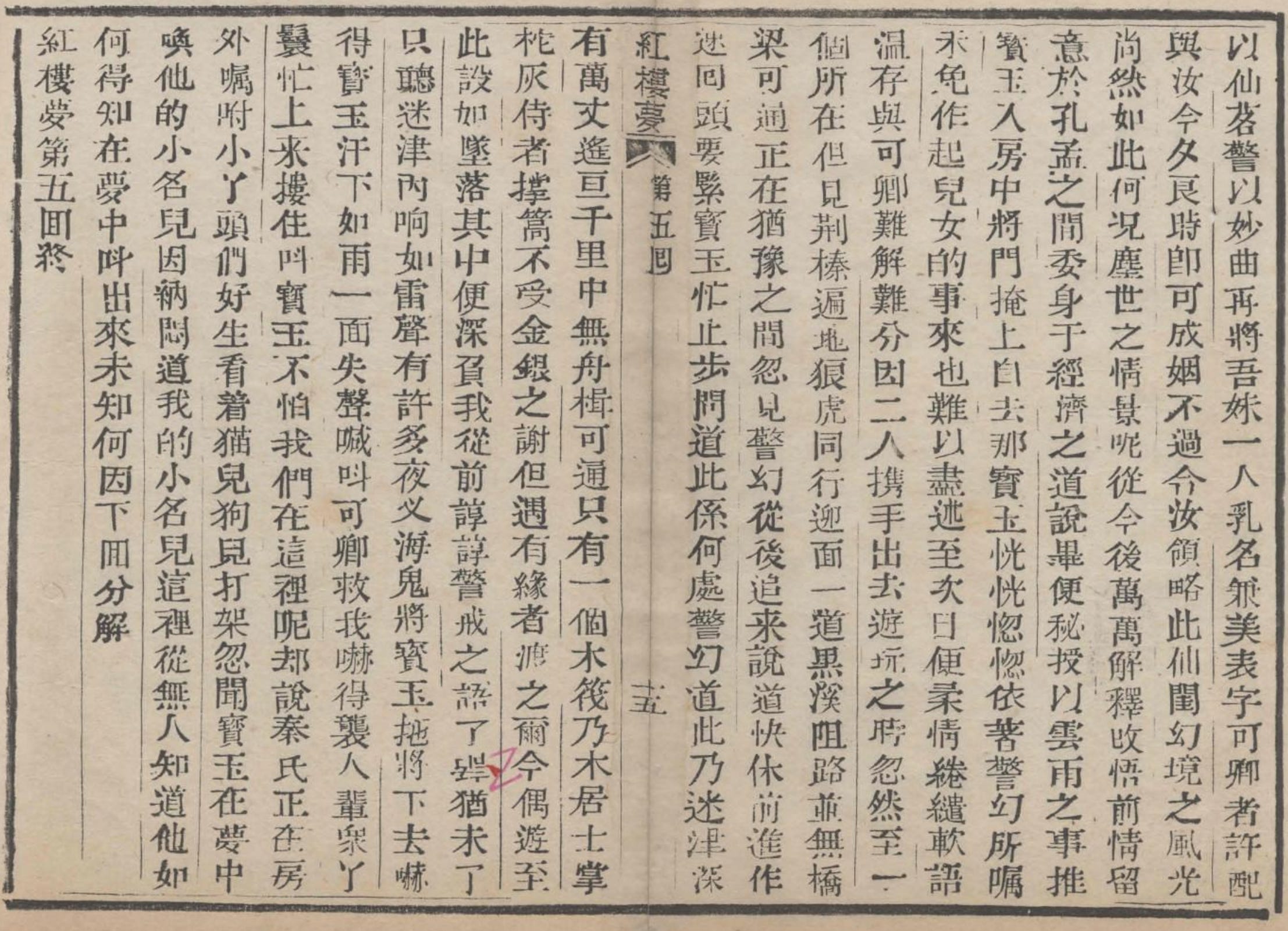

寶玉聽了,嚇的慌忙答道:「仙姑差了。我因懶於讀書,家父母尚每垂訓飭,豈敢再冒『淫』字?況且年紀尚幼,不知『淫』為何事。」警幻道:「非也。淫雖一理,意則有別。如世之好淫者,不過悅容貌,喜歌舞,調笑無厭,雲雨無時,恨不能盡天下之美女供我片時之趣興,此皆面板濫淫之蠢物耳。如爾,則天分中生成一段痴情,吾輩推之為意淫。惟『意淫』二字可心會而不可口傳,可神通而不可語達。汝今獨得此二字,在閨閣中雖可為良友,卻於世道中未免迂闊怪詭,百口嘲謗,萬目睚眥。今既遇爾祖寧榮二公,剖腹深囑,吾不忍子獨為我閨閣增光,而見棄於世道,故引子前來,醉以美酒,沁以仙茗,警以妙曲,再將吾妹一人,乳名兼美,表字可卿者,許配與汝。今夕良時,即可成姻。不過令汝領略此仙閨幻境之風光尚然如此,何況塵世之情景呢?從今後,萬萬解釋,改悟前情,留意於孔孟之間,委身於經濟之道。」說畢,便祕授以「雲雨」之事,推寶玉入房中,將門掩上自去。

那寶玉恍恍惚惚,依著警幻所囑,未免有兒女之事,難以盡述。

至次日,便柔情繾綣,軟語溫存,與可卿難解難分。因二人攜手出去遊玩之時,忽至一個所在,但見荊榛遍地,狼虎同群,迎面一道黑溪阻路,並無橋樑可通。正在猶豫之間,忽見警幻從後追來,說道:「快休前進!作速回頭要緊!」寶玉忙止步問道:「此係何處?」警幻道:「此乃迷津,深有萬丈,遙亙千里,中無舟楫可通,只有一個木筏,乃木居士掌柁,灰侍者撐篙,不受金銀之謝,但遇有緣者渡之。爾今偶遊至此,設如墜落其中,便深負我從前諄諄警戒之語了。」話猶未了,只聽迷津內響如雷聲,有許多夜叉海鬼,將寶玉拖將下去。嚇得寶玉汗下如雨,一面失聲喊叫:「可卿救我!」嚇得襲人輩眾丫鬟忙上來摟住,叫:「寶玉,不怕,我們在這裡呢。」

卻說秦氏正在房外囑咐小丫頭們好生看著貓兒狗兒打架,忽聞寶玉在夢中喚他的小名兒,因納悶道:「我的小名兒,這裡從無人知道,他如何得知,在夢中叫出來?」

未知何因,下回分解。

Translation Notes

訓飭 (xùnchì) means to strictly chastize and correct somebody. 垂 means to deign or condescend to do something. In other words, 每垂訓飭 really should read something like “every time they see fit to reprimand me.”

淫 (yín) is almost impossible to translate in this context. 淫 means extravagant or wild in a sexual sense, and usually means something like licentious or lewd. In our most recent translation post we saw that the Goddess called Baoyu more filled with 淫 than any other person in the world. I translated it as “passion” at the time to give it a positive spin – and to make the word 淫 make sense in the sense that the Goddess was explaining it. Here, however, Baoyu clearly sees 淫 as something awful – “lustful” would probably be the correct term. The Goddess points this out when she replies 淫雖一理,意則有別.

We saw 雲雨 yesterday; it’s a common euphemism for sex in classical Chinese.

痴情 here must mean something like “emotional passion.” 情 has showed up once again, of course. 痴 can mean “foolish” or “obsessive,” but here it likely means something more like “infatuated.” In other words, the thing that sets Jia Baoyu apart from the other passionate or lustful people is his obsession with making emotional connections with others.

迂闊怪詭 (yūkuòguàiguǐ) means impactical, strange, eccentric, illogical, and so on.

睚眥 means to stare in anger.

剖腹 literally means to cut open the abdomen or disembowel. Here it means to speak from the heart.

沁 here actually means to immerse or soak. It’s part of a parallel set of three verbs: 醉 (to make drunk), 沁 (to immerse or soak), and 警 (to warn).

兼美 (jiānměi) literally means “combined beauty.” This is why this celestial maiden is described as embodying the beauty of both Lin Daiyu and Xue Baochai. Meanwhile, 可卿 means “acceptable minister.”

The Goddess orders Baoyu to 改悟前情, or to abandon his past emotional obsession (前情) and become enlightened (改悟). Here 情 is presented as something negative, even though the Goddess just described Baoyu’s capacity for 情 as a unique divine gift. She’s ordering him to abandon his true nature in the name of his social duty.

木居士, or “the Hermit of Wood,” is a Taoist symbol of the unconditioned and simple natural state – a state free from worldly desires. Meanwhile, 灰侍者, or “the Servant of Ashes,” represents the end of the fire of desire – the burning up of all the passions and dust of the material world. To cross the Rubicon, Jia Baoyu would need to completely free himself from all worldly passions and desires. Baoyu seems to not be ready yet, since he still is attached to emotions and passions (情).

諄諄 means earnest and sincere.

夜叉 means yaksha in Buddhism; it’s a malevolent spirit.

Thank you for your fine translation! Awesome work.

The Yangs referred to multiple editions for their translation. The poem at the end of chapter 5, which is not present in the edition you're translating (and which Hawkes and the Yangs also primarily followed), the printed 程乙本 (from 1792), appears in the handwritten 甲戌本 version (from 1754), known as the "Jiaxu manuscript", an early copy of "Zhiyanzhai's Repeated Commentary on the Story of the Stone" (脂硯齋重評石頭記).

You can find this version on Wikisource: https://zh.m.wikisource.org/wiki/脂硯齋重評石頭記甲戌本 (I'd recommend the more comprehensive https://zh.m.wikisource.org/wiki/脂硯齋重評石頭記, which includes not just the 甲戌本 edition, from 1754, but also two other handwritten versions: 己卯本, from c. 1760, and 庚辰本, from c. 1761).

I believe you'll enjoy the commentary, and it may be helpful in your analysis.

For reference, here's the poem in Chinese:

一場幽夢同誰訴,千古情人獨我知。

Can we assume that the line "from now on you must utterly renounce these attachments [...] study mendicus and confucius." is an allusion to the 才子佳人 novels? Either way, it's amusing that immediately after they stumble on the "River of Delusion".

Great end to a great chapter. Really sets us up with understanding what the sort of failure conditions are going forward.