The Metaphysics of Jia Baoyu

I’m going to warn you in advance. Today’s post is long and kind of boring.

It’s done this way by design, actually. We’ll talk a little bit tomorrow about Jia Yucun’s style of lecturing here.

There’s some interesting stuff here, though I’d warn you against taking this stuff too seriously. And, as we’ll see tomorrow, Jia Yucun doesn’t really know what he’s talking about.

This is one of those passages where you absolutely need a commentary or two to figure out what in the world is going on. And, as you guessed, the original author Cao Xueqin wrote it this way on purpose.

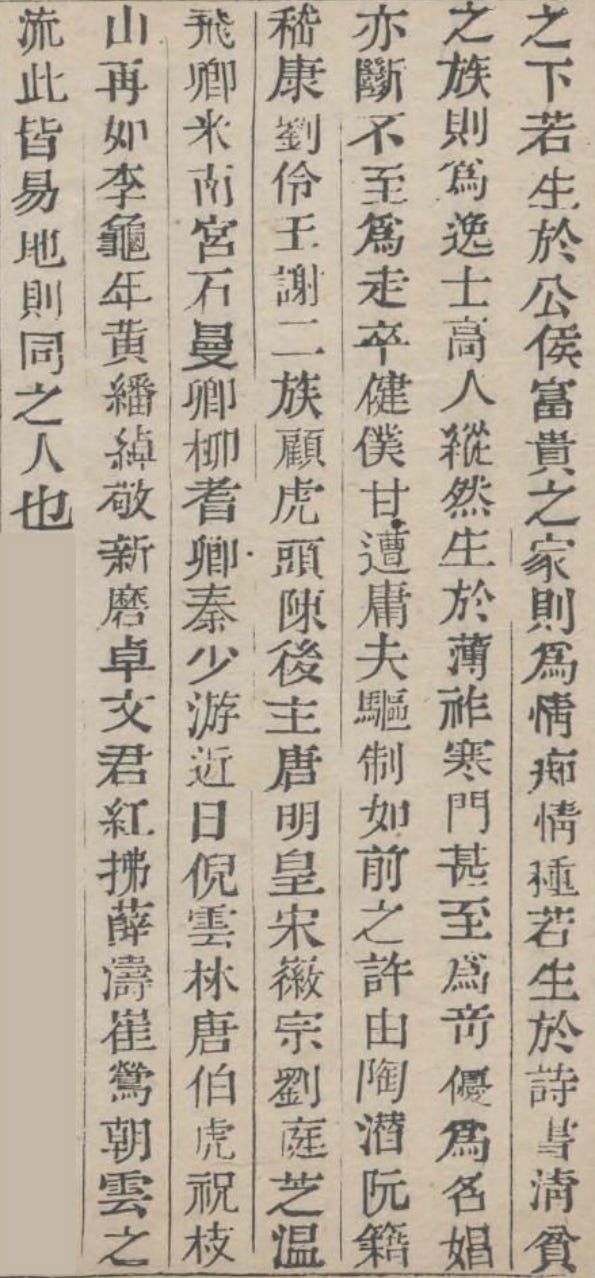

Chinese Text

雨村罕然厲色道:「非也。可惜你們不知道這人的來歷。大約政老前輩也錯以淫魔色鬼看待了。若非多讀書識事,加以致知格物之功,悟道參玄之力者,不能知也。」

子興見他說得這樣重大,忙請教其故。雨村道:「天地生人,除大仁大惡,餘者皆無大異。若大仁者,則應運而生;大惡者,則應劫而生。運生世治,劫生世危。堯、舜、禹、湯、文、武、周、召、孔、孟、董、韓、周、程、朱、張,皆應運而生者;蚩尤、共工、桀、紂、始皇、王莽、曹操、桓溫、安祿山、秦檜等,皆應劫而生者。大仁者修治天下,大惡者擾亂天下。清明靈秀,天地之正氣,仁者之所秉也;殘忍乖僻,天地之邪氣,惡者之所秉也。今當運隆祚永之朝,太平無為之世,清明靈秀之氣所秉者,上自朝廷,下至草野,比比皆是。所餘之秀氣,漫無所歸,遂為甘露,為和風,洽然溉及四海。彼殘忍乖僻之邪氣,不能蕩溢於光天化日之下,遂凝結充塞於深溝大壑之中,偶因風蕩,或被雲摧,略有搖動感發之意,一絲半縷,誤而逸出者,值靈秀之氣適過,正不容邪,邪復妒正,兩不相下,如風水雷電,地中相遇,既不能消,又不能讓,必至搏擊掀發後始盡。既然發洩,此氣亦必賦之於人。假使或男或女,偶秉此氣而生者,上則不能為仁人為君子,下亦不能為大凶大惡,置之千萬人之中,其聰俊靈秀之氣,則在千萬人之上;其乖僻邪謬不近人情之態,又在千萬人之下。若生於公侯富貴之家,則為情痴情種;若生於詩書清貧之族,則為逸士高人;縱然生於薄祚寒門,甚至為奇優,為名娼,亦斷不至為走卒健僕,甘遭庸夫驅制。如前之許由、陶潛、阮籍、嵇康、劉伶、王謝二族、顧虎頭、陳後主、唐明皇、宋徽宗、劉庭芝、溫飛卿、米南宮、石曼卿、柳耆卿、秦少游,近日倪雲林、唐伯虎、祝枝山,再如李龜年、黃翻綽、敬新磨、卓文君、紅拂、薛濤、崔鶯、朝雲之流,此皆易地則同之人也。」

Translation Notes

Hold onto your hats — this is going to be a bumpy ride.

致知格物之功 is clearly a Confucian line. The phrase 致知格物 comes from the 大學 (Great Learning): “致知在格物,” or “extend one’s knowledge through the investigation of things.” 功 here means “disciplined effort” or “cultivated skill.”

悟道參玄之力, in contrast, is a Taoist line. 悟道 is to become enlightened to the Tao, and 參玄 means to deeply understand the profound. The overall idea is to have penetrating insight into the profound.

In other words — Jia Yucun is claiming that his formal Confucian learning and his supposed Taoist insight has allowed him to discern why Jia Baoyu (who he’s never seen or met) is so eccentric.

In the phrases 應運而生 and 應劫而生 the concepts of 運 (auspicious) and 劫 (inauspicious) are directly related. The idea here is that virtuous ages give birth to virtuous people, and ages of calamity give birth to people who bring chaos about.

Jia Yucun refers to the following 16 “virtuous people:”

堯 refers to the legendary Emperor Yao.

舜 refers to Emperor Shun, another legendary Emperor.

禹 refers to Yu the Great, the legendary king associated with the foundation of the Xia dynasty.

湯 refers to Tang of Shang, the first king of the Shang dynasty.

文 refers to King Wen of Zhou.

武 refers to King Wu of Zhou.

周 refers to 周公旦, commonly referred to as the Duke of Zhou.

召 refers to 召公奭, commonly referred to as the Duke of Shao.

董 refers to Dong Zhongshu (董仲舒), a famous philosopher of the Han dynasty.

韓 refers to the famous Chinese philosopher Han Yu.

The second 周 likely refers to Zhou Dunyi.

程 probably refers to both Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi, known as the Cheng brothers (or the two Chengs: 二程).

朱 refers to the famous philosopher Zhu Xi.

張 likely refers to Chinese philosopher Zhang Zai.

Jia Yucun then refers to the following 10 “chaotic” people:

蚩尤 is Chiyou, a mythological king associated with chaos and war.

共工 is Gonggong, an ancient Chinese water diety often blamed for various cosmic catastrophes.

桀 refers to Jie of Xia, regarded as a tyrant who brought about the collapse of a dynasty.

紂 is King Zhou of the Shang dynasty.

始皇 refers to the tyrant Qin Shi Huang.

王莽 is Wang Mang, the founder and only emperor of the short-lived Xin dynasty. His political efforts resulted in chaos.

曹操 is Cao Cao of Three Kingdoms fame.

桓溫 is Huan Wen, an ancient general whose campaigns ended up largely in failure.

安祿山 is An Lushan, a rebel general during the Tang dynasty; his rebellion devastated the country and killed millions.

秦檜, Qin Hui, was a counselor during the Song dynasty who is blaimed for being a traitor.

If you look carefully at both lists of names, you’ll notice that they follow a basic chronological and doctrinal hierarchy. This is how we know that Zhou Dunyi is the second 周: the fact that he is listed between Han Yu and the two Chengs means that it’s almost certainly Zhou Dunyi. Among other things, Cao Xueqin is showing here how mechanical and orthodox this idea of “auspicious” and “inauspicious” was in mainstream Chinese thinking at the time.

靈秀 means exceptionally beautiful, elegant, intelligent, and talented – a rare combination of qualities that makes somebody truly special. “Excellent” is kind of a lame translation, but it works here with the repetitive and formulaic flow of the lines.

草野 literally means the countryside, and is often used to refer to the common people or the masses.

洽然 means moisture-like: it’s an adverb for the word 洽, which means to moisten.

一絲半縷 is a phrase that means something like “a small thread.” Since we’re talking about mystical “evil” air and vapor, it’s best to call it a “wisp.”

妒 means to be jealous; here it’s probably best as “to resent.”

如風水雷電,地中相遇 represents clashing forces: a hidden (or underground – 地中) conflict between the elements. Interestingly, this resonates with the I Ching: if you look up these four elements, you’ll see that they are all in conflict with each other.

逸士 means an “untethered” scholar, and, by extension, implies that the scholar is a recluse.

薄祚 means something like “weak fate.” 祚 means blessing. 寒門 means a “cold gate.” The implication here is that the person had th殘忍乖僻之邪氣e unfortunate fate of being born into a poor household.

奇優 is a kind of opera performer – traditionally socially despised. 名娼 literally means a “famous prostitute.”

甘遭庸夫驅制 means “willingly be subjected to being driven around by mediocre men.” Cao Xueqin is saying here that the noble souls who find themselves in poverty would still much rather become artists and courtesans than menial servants – even though the menial servants were technically of higher social standing.

Jia Yucun refers to the following 17 artistically minded people from the past:

許由, or Xu You, was a legendary Chinese recluse who lived during the reign of Emperor Yao.

陶潛 refers to the famous poet Tao Yuanming.

阮籍 is Ruan Ji, a famous musician and poet during the end of the Eastern Han dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period.

嵇康 is Ji Kang, a literary artist of the Three Kingdoms period.

劉伶 is Liu Ling, a Chinese poet.

王謝二族 refers to the Wang and Xie families, who were powerful during the Six Dynasties period in Chinese history. The Wang family dominated the court of Eastern Jin. The Xie family were known for military prowess. Both were instrumental in the development of Chinese art.

顧虎頭 is Gu Kaizhi, a famous painter.

陳後主 refers to Chen Shubao, a ruler much more interested in literature and women than state affairs.

唐明皇 is Tang Minghuang, a Tang dynasty emperor famous for pleasure seeking and womanizing.

宋徽宗 is Emperor Huizong of Song, known for his love of art and incompetence in governing.

劉庭芝 is Liu Tingzhi, a Tang dynasty official known for his excellent literature.

溫飛卿 is Wen Tingyun, a famous Tang dynasty poet.

米南宮 is Mi Fu, a famous painter and poet.

石曼卿, Shi Manqing, was a famous literary figure in the Song dynasty.

柳耆卿 is Liu Yong, a famous Chinese poet of the northern Song dynasty.

秦少游 is Qin Guan, a famous poet of the Song Dynasty.

Jia Yucun then refers to the following 3 artists associated with more recent dynasties:

倪雲林 is Ni Zan, a famous painter during the Yuan and Ming dynasties.

唐伯虎 is Tang Yin, a Chinese painter and calligrapher.

祝枝山 is Zhu Yunming, a Chinese calligrapher of the Ming dynasty.

Note that all three of these historical figures were actually revolutionary in their own fields.

Finally, Jia Yucun refers to the following 8 legendary figures:

李龜年 is Li Guinian, a Tang dynasty musician.

黃翻綽 is Huang Fanchuo, a legendary Tang dynasty court entertainer with a lot of wit an humor.

敬新磨 is Jing Xinmo, an artist in the Tang dynasty referred to as a court jester here.

卓文君 is Zhuo Wenjun, a poet we’ve talked about before.

紅拂, Hong Fu or Zhang Chuchen, is a legendary Chinese folk heroine.

薛濤 is Xue Tao, a courtesan and poet during the Tang dynasty.

崔鶯 is Cui Yingying, a character in the famous story “The Biography of Ying-ying” (鶯鶯傳).

朝雲 is Wang Chaoyun, a celebrated courtesan and poet of the Tang dynasty.

Notice that the final 5 figures are all women — though, of course, one is actually a fictional character.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

Hawkes actually does a good job with this section.

Hawkes takes the difficult “若非多讀書識事,加以致知格物之功,悟道參玄之力者,不能知也” and translates it as “This is something that no one but a widely read person, and one moreover well-versed in moral philosophy and in the subtle arcana of metaphysical science could possibly understand.” This is a spot-on translation that hits both the Confucian “bookish” part of Jia Yucun’s statement as well as the “mystical” Taoist part.

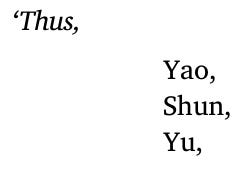

In The Translator’s Mirror for the Romantic, Professor Fan Shengyu correctly points out that David Hawkes handles Jia Yucun’s ridiculous lists masterfully. You have to see it to understand it:

And, later on:

There’s really no effective way for me to format this on Substack (or Wordpress, or really anywhere else) to show what David Hawkes did here.

The reason why this approach is brilliant, of course, is because it emphasizes the matter-of-fact nature of what Jia Yucun is saying. Jia Yucun is basically rattling off a list of famous names in an attempt to show his erudition and understanding.

Note, however, that Hawkes doesn’t quite identify every single one of the people listed.

Hawkes also does a good job of writing in a boring and overly formal style that emulates Jia Yucun’s speaking style here. We get a number of paragraphs that start with the italicized words now, therefore, moreover, consequently, and now. Hawkes also uses a ridiculously complicated translation of Jia Yucun’s vague and wannabe scientific terms: the “cruel and perverse humours,” for example, sink down “by a process of incrassation and coagulation,” and are later referred to as “incrassate humours.” He also refers to an “errant flocculus” and uses a few other words that are pretty difficult to understand.

If you’re reading Hawkes’ Story of the Stone and are wondering what in the world is going on, let me give you a brief gloss of the more difficult English words he uses:

Humour, a word that you and I probably feel that we already know, is used here in its archaic sense. It refers to liquid that flows in the body of animals — blood vessels and the like.

Asperge means to sprinkle: therefore, the “pure, quintessential humour” that is “asperged and effused for the enrichment and refreshment of all terrestial life” are just sprinkled about in the air to help people out.

Incrassation is the process of thickening. The bad “humour” thickens into a sort of solid and gets stuck in the ditches and ravines. These are later referred to as “incrassate humours,” which you can think of as something like a ball of evil.

Flocculus is a small and fluffy tuft; it’s best to think of this as a cloud (which is what the Chinese original says).

Hetaerae is the plural form of the word hetaera, a word that originally comes from ancient Greek (ἑταίρᾱ). It refers to highly cultivated female companions that would accompany rich and older men — high class prostitutes.

Yang

The Yangs helpfully provide footnotes explaining who the people Jia Yucun mentions actually are. The translation is also more straight forward than the one Hawkes gives, though it’s missing a lot of the ironic pseudo-bookish language that Jia Yucun uses.

Note that the Yangs don’t provide much explanation in their footnotes aside from a very basic explanation of who the person was and which dynasty they lived in. For example, they don’t call much attention to the fact that “Tsui Ying-ying” is a comletely fictional character. They also neglect to tell us who “Cho Wen-chun” is, perhaps because we already saw a reference to her earlier in the book.

Both Hawkes and the Yangs fail to explain why we’ve suddenly run into this big and overwhelming list of names, though at least Hawkes shows us the absurdity of it all.