The Zhongshan Wolf

We’ll keep this poem cryptic for a while. There are no textual puns that hint at who the girl described here is. Her identity isn’t revealed until much later in the story, and it’s only really made clear through what happens to her.

My Translation

Next was a painting of a fierce wolf chasing and striking a beautiful woman, as if he was going to eat her. Beneath it was this poem:

He’s just like the Zhongshan Wolf,

Becoming savage after enjoying success.

The delicate flower from the golden room

Went to the world of dreams within a single year.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

David Hawkes adds a bit of flair to the picture that isn’t present in the original. He write that the wolf “had just seized her with his jaws and appeared to be about to eat her.” That’s not quite what the original says. 追撲 means to chase and strike, and 有欲啖之意 means that the wolf looked like he wanted to eat her.

Hawkes’ poem needs a line by line commentary.

The first line is:

Paired with a brute like the wolf in the old fable

Of course, no normal English reader knows what “old fable” we’re talking about, and there are no textual notes to help us out. David Hawkes does explain the “old fable” in the appendix, though you have to basically spoil a major part of the book if you want to see the explanation.

The second line:

Who on his saviour turned when he was able

In the story of the Zhongshan Wolf, the wolf decides to attack the person who rescues him from the hunter. The religious implications of turning on one’s “saviour” are not present in the Chinese original at all.

The third and fourth lines are confusing:

To cruelty not used, your gentle heart

Shall, in a twelvemonth only, break apart

Twelvemonth is an obsolete term for a year. While the Chinese term 一載 (one year) was a little archaic, it would have been easily recognizable to readers in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Note that the Chinese original does not refer to this girl as having a “gentle heart.” Rather, she is a delicate flower (花柳質) from the golden chamber (金閨).

Also, there’s nothing in the original about a “heart breaking apart.” Instead, the phrase is 赴黃粱, which means to go to a dream world (see the translation note below). It’s not clear if 黃粱 refers to death specifically, but there certainly is a strong implication of that.

In other words — David Hawkes isn’t just interpreting the poem as part of his translation. He’s actually changing the meaning.

Yang

The Yangs translate 中山狼 as “a mountain wolf,” which misses the sense of ingratitude. They translate 赴黃粱 as “a rude awakening,” which is actually the opposite of what the original Chinese means.

Chinese Text

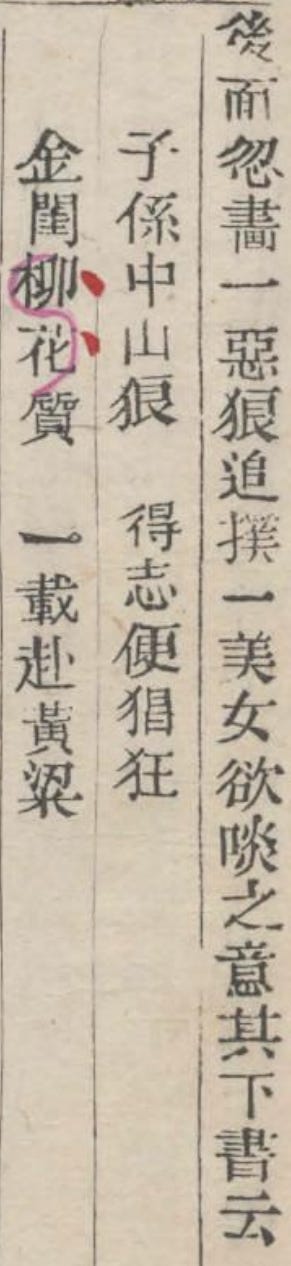

後面忽畫一惡狼,追撲一美女,有欲啖之意。其下書云:

子系中山狼,得志便猖狂。金閨花柳質,一載赴黃粱!

Translation Notes

撲 (pū) means to beat or strike

啖 (dàn) means to eat or feast on.

中山狼, “The Zhongshan Wolf,” is the title of a traditional Chinese opera. The story is about how Lord Jian of Zhao was hunting in Zhongshan during the Warring States era. He found a wolf, and was about to kill it. However, a scholar named Dongguo intervened and saved the wolf. The wolf later turned on Dongguo, though, and tried to harm him. The phrase is used to describe a person who repays kindness with ingratitude – a treacherous, ungrateful villain.

得志 means to achieve your ambitions or to enjoy success.

猖狂 means savage, furious, or aggressive.

赴 (fù) means to go

黃粱 almost certainly refers to the 枕中記 or 黃粱記, a traditional Chinese story about a dream that a Daoist monk once had. The idea behind the story is that life itself is an illusion – a theme that is pretty common in Dream of the Red Chamber.

Excellent -- very clear translation and commentary. I find it very helpful.

There is a small error in the transcription of the first stanza of the poem, however:

「子系中山狼 」should be 「子係中山狼」

how many of these poems and plays would the average chinese person at the time of writing know or understand the references to? It seems like a grand display of the breadth of knowledge of the author(s) (and you in turn!) to get all of this into this book. time and time again your translation has served as a jumping off point to explore a whole range of other works.

p.s. I was on a bit of a break from reading the translations because I dove deep into arthurian and germanic mythology but now it's time to catch up.